In this illuminating piece, Molly Navey and Ellie Obsorne from Priory School in Lewes explain why and how they have worked hard to decolonise their Key Stage 3 curriculum. They provide an excellent rationale and free downloadable resources too.

Back in the grips of lockdown, our department decided the curriculum needed a revamp. Whilst the department had been working towards diversifying the curriculum for some time, there were still a lot of gaps.

We decided the best way to progress was to design a meaningful Key Stage 3 curriculum that we could improve upon each year.

Having made a start, in 2020 we agreed to run a CPD session across school on improving diversity in each subject area.

This prompted lots of interesting discussion but made us realise we hadn’t really got to the depths of the problem: increasing representation is clearly important but what about pupils’ understanding of where diverse history comes from and who is writing this history?

Why did we want to move towards decolonisation?

Quite rightly many departments have begun to reshape their curriculum in the last couple of years around their local context and in response to recent political movements.

This formed part of our rationale. However, we were also heavily influenced by our shared principle that all pupils are entitled to be taught genuinely authentic history; if we want pupils to be able to model historians’ research methods, they need a clear understanding of who historians are and what they argue about.

Combined, this has led us to try to encompass the whole spectrum of people’s lived experience across our Key Stage 3 curriculum, whether gender, sexuality, race, religion, class or disability.

What do we mean by decolonising the curriculum?

The term decolonisation has a complex history in itself. Whilst it has had political meaning since colonies begun campaigning for independence in the 1950s, it wasn’t until the 1990s that it started to be widely used in educational terms.

Historians increasingly saw the importance of switching the lens to focus on a diverse range of experiences. In some cases, this meant changing their research methods, as well as the focus of their research.

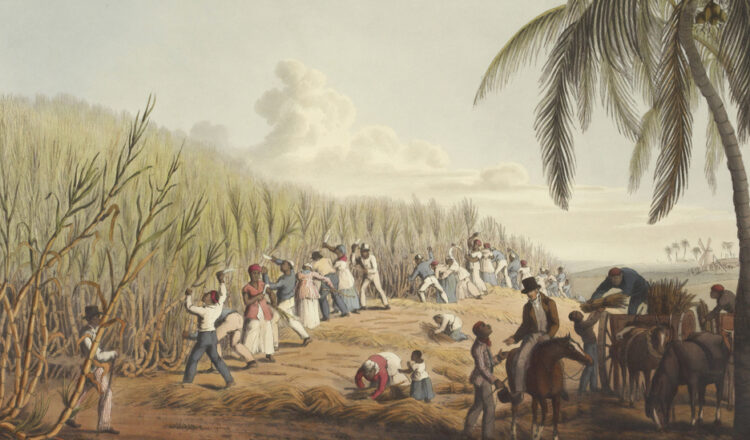

By the early 2000s, history teachers begun to pay more attention to issues of diversification and decolonisation, including Traille (2007) who argued that trans-Atlantic slavery must be taught within a broader context of Black history.

More recently, Jackson (2021) has pushed forward these ideas through her wider work on decolonisation and the useful questions we can ask as part of this process.

Having been influenced by these key ideas, our history department begun to move towards decolonising our curriculum.

Whilst diversification certainly has its place in the curriculum, as we ensure our pupils are taught multiple different narratives, we are most interested in explicitly teaching pupils that there are not just different narratives but multiple perspectives about the past.

As historically pupils have been taught history through a white European lens, we are seeking to address this imbalance by challenging the idea that this is the only historical lens.

This isn’t about pulling the whole curriculum apart or getting rid of white European perspectives. Instead, we are suggesting widening the lens so that pupils gain a more balanced view of each historical narrative taught.

We have taken a three-step process in our efforts to decolonise our curriculum.

Step 1: Stories of individuals

We have found one of the most effective ways to make quick and meaningful changes to our curriculum is through the use of individual stories.

These have had a big impact on pupils’ historical understanding without requiring lots of planning time.

Starting each enquiry with the story of an individual has helped the knowledge stick in pupils’ heads.

We have found this to be a strong starting point for decolonising the curriculum, if these stories are used to broaden the perspectives encountered.

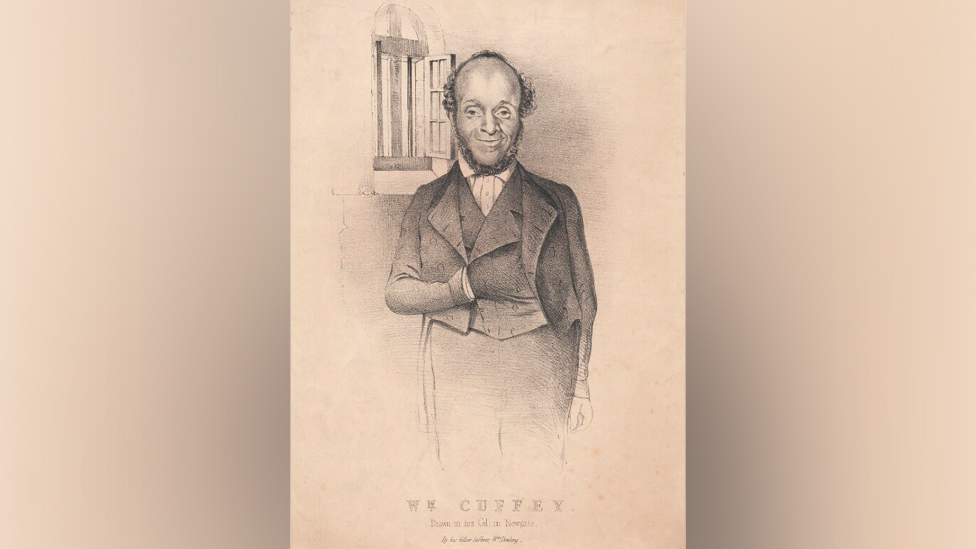

One of our most effective examples is introducing Year 8 pupils to an enquiry on democracy in Britain through the stories of William Lovett, William Cuffay and Elizabeth Hanson (see Downloadable Resource Pack for these stories).

By encompassing the stories of working-class campaigners of different genders, disabilities and races, pupils are better able to see the complexity of the past and the intersectionality of experiences.

Step 2: Non-traditional sources in lessons

A key focus for us this year has been increasing the use of non-traditional sources in order to reflect the various methodologies used by historians.

For example, we have used oral histories, songs and art as the basis of lessons.

This helps to decolonise each enquiry as it gives a voice to the individuals who may not otherwise be represented in ‘traditional’ sources.

One of our most successful attempts has been our newest Y9 enquiry tracking the American Civil Rights Movement from the American Civil War to the end of the 1980s.

Throughout this enquiry, pupils encounter the songs, art and poetry of those affected by racism in 20th-Century America.

For example, the work of Black artists, such as Langston Hughes, Archibald Motley, Jacob Lawrence and Ma Rainey are used when studying the Harlem Renaissance.

They use the art produced by the movement to learn about the wider aims of the Civil Rights Movement, such as the celebration of African cultures.

We have also sought to use oral history across a range of enquiries so that pupils see and recognise the value of this throughout the curriculum and as a methodology used by historians. In Y7 they encounter the oral history of the Sunjata Epic, whilst in Year 9 they listen to the stories of LGBTQ+ people as part of an enquiry focused on British society post World War2 .

Step 3: Range of historians

We recognise that it is not just what we teach and how we teach it that is important but also who the knowledge is coming from.

As a result, we have actively sought to ensure that the historians pupils encounter are from a wide range of backgrounds, both in their personal and academic experiences.

When pupils study World War 2, they learn the experiences of Indian soldiers through Yasmin Khan’s The Raj at War.

David Olusoga’s Black and British has also been transformational in shaping our approach to British History across the curriculum.

The key is to dip into the scholarship and use relevant extracts with your pupils!

So, what now?

Whilst we feel that in the past few years we have made considerable progress in decolonising our curriculum, we recognise that this is something that will need continuous adaptation and change.

Our key areas of development for the future are to ensure that our curriculum focuses as much on class and disability as we currently do on race and gender.

As well as this, we hope to increase the range of historians we use so that our pupils encounter not just a plethora of perspectives but a broader understanding of historical scholarship in their Key Stage 3 curriculum.

Download Resources

Molly Navey and Ellie Osborne are history teachers at Priory School in Lewes. They are also both mentors for Initial Teacher Education history trainees with the University of Sussex.