Claire Hollis reflects on making the A level curriculum more representative. Claire explains the barriers she faced and offers clear solutions to help you to provide a more representative curriculum .

In 2018 I was a new head of department, full of ideas about representation in the curriculum, many of them gleaned from the inspiring work done by other teachers.

However, there was just one problem.

My new job put me in charge of the History curriculum at a sixth-form college. This meant that looming over all my efforts was the shadow of the exam specification and the attendant concern about preparing my students to be successfully tested on it.

Faced with these problems it might seem reasonable to focus work on representation on the more flexible world of Key Stage 3, while holding out for another round of reforms to the specifications.

Yet while I would cheer this on with all enthusiasm, I believe that there is much we can do at Key Stages 4 and 5 while we wait.

I have written elsewhere about why I believe representation is fundamental to giving students a good historical education.

The benefits it brings to students’ understanding of individual periods, of the world of the past and their ability to engage with the discipline as it is currently practiced, are no less important at Key Stages 4 and 5.

But how to navigate the barriers placed in our path by the specification and its requirements?

Over the last few years, my department has found that there is space in the A-level curriculum for both routine representation where elements are woven in to our existing teaching, and deep representation where enquiries are reconfigured to place underrepresented stories at their heart.

I am going to share some examples of our work below. More importantly, I will share some of the organising principles we devised to guide it, which might be usefully applied to your specific context.

How do you find the gaps in the specification?

Sometimes you find yourself teaching a topic that you sense is not landing in the way you want it to.

My particular frustration was with our introduction to the economic crisis in the Ancien Regime, at the start of our course on the French Revolution.

The specification required us to cover problems of royal finance and the attempts of Louis XVI’s Controller-Generals to address them.

Accordingly, one of the first images our students encountered was a line of bewigged finance ministers, and the picture of France’s economic problems they built up was dominated by these ministers’ doomed attempts to resolve them.

But what did the economic crisis mean for the people of France? Why did so many of them resist attempts to address it?

I could tell that this top-down approach was not helping my students to explore these questions.

This brings me to my first indicator that there is a gap in the specification, the sense that the existing way of approaching a topic is giving students a less rich and complete picture of the topic in question than you would like.

Step forward Madeleine Pochet. A working woman from a small town near Paris, she was a key figure in the bread riots that engulfed France in 1775 which have become known as The Flour War.

I had first encountered her story at university and I had a hunch that she might be the key to solving my problem.

The next time I introduced France’s economic crisis therefore, we started by joining Madeleine as she saved up money to buy necessities for her family, went to market to find that grain was scarce and her neighbours were panicking.

She then led them in a carefully choreographed raid on the grain stores, organising the distribution of their contents.

With this one story, not only were my students engaging with the life of an ordinary woman in pre-revolutionary France, they were also better-equipped to engage with some of the questions I wanted them to think about.

Madeleine allowed them to see the economic crisis and the reforms being introduced to address it from the perspective of someone whose life was profoundly affected by them.

Her resistance to Turgot’s attempt to introduce a free market in grain also showed the students why obstruction of economic reforms made sense to people, and gave them an idea as to why it was so widespread.

Finally, a few weeks later when we encountered the people of Paris in 1789, Madeleine could be invoked once again to give students an idea of their mindset.

This illustrates the other two indicators of a gap in the specification.

Madeleine was an example of a relevant story that was not being represented.

Her story was also going to add depth and detail to students’ understanding of the topic at hand, and would help them reason about it more effectively.

Once you’ve found your gaps in the specification, how do you make the best use of them?

Some key concerns teachers have about including routine representation at Key Stages 4 and 5 are about the time available to cover the required material and concerns about tokenism.

In both instances, the solution lies in making sure the stories you represent are making a significant contribution to your students’ understanding of the topic you are teaching.

The first way in which routine representation can do this is by adding detail and richness to students’ understanding of events and therefore improving their ability to reason about them.

Madeleine Pochet provides a good example of this; her story not only served as a window into the experience of the ordinary women who took an active role in the events of the French Revolution, but also gave students an insight into the motivations of people resisting economic reforms that they might not otherwise have had.

The second way in which representation can work for you is by providing alternative interpretations of events and allowing students to wrestle with them.

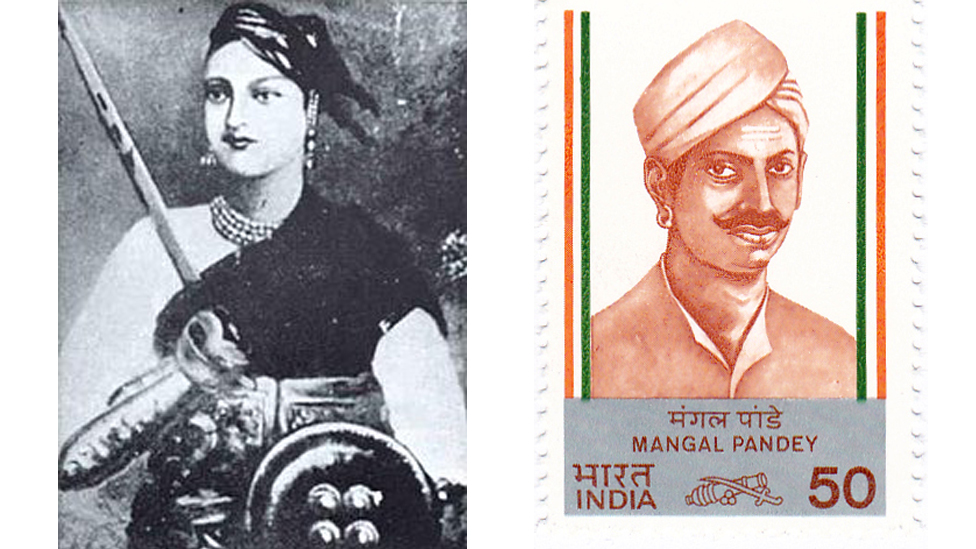

In our teaching of the British Empire course the stories of the Rani of Jhansi and Mangal Pandey are crucial to the representation of Indian perspectives on the events of 1857.

They also allow students to challenge the interpretation of these events as a mutiny by giving them an insight into wide-ranging grievances against the East India Company, and participation in the rebellion by groups outside of the army.

Both these examples also point to the third way in which representation can make a meaningful contribution. This is by reframing events, themes and processes studied and allowing students to think about them in a different way.

Across the board, the key consideration that should drive choices made about routine representation at Key Stages 4 and 5, is which underrepresented stories are going to make a difference to your students’ understanding when they encounter them.

Is routine representation the only method we can use?

As the requirements of the specifications restrict the kinds of stories we are able to tell, it may seem that using routine representation may be the best that we can hope for at Key Stages 4 and 5.

However, in some cases, I have found that creative reframing of how I approach certain topics has allowed me to meet the demands of the specification, while putting underrepresented perspectives at the heart of the enquiry.

One example is in the work we have done on our British Empire course. Last summer we embarked on some serious rethinking of the scheme of work, as we had found the thematic structure outlined in the textbook had left some of our students confused.

I also wanted to use the opportunity to put the perspective of people living under British rule at the heart of certain enquiries.

The enquiry question that had driven our study of India between 1857 and 1890 was “How Far did British Rule in India change between 1857 and 1890?”.

This had been constructed to meet the requirements of the specification, which set out key aspects of British government in India that students had to understand.

However, I felt this enquiry was a bit lacklustre and I was especially dissatisfied with the failure of this question to allow for an in-depth study of the experience of the Indian population.

The enquiry we have designed to replace it is driven by the question, “Why did Indian Responses to British Rule Develop into Nationalism by 1914?”

This allows us to cover the elements of the Raj outlined in the specification, but places the focus on how the Indian population experienced and reacted to them; it was also a much more interesting story.

Extending the chronological scope of the enquiry and looking at the development of nationalism allows students to engage with a genuine historical debate about when and how this developed in India.

It also prepares them to encounter nationalism in other parts of the empire as they move through the course and sets them up to answer relevant questions on exam papers.

Of course, this is not always possible. As yet, I have not found a way of restructuring our enquiry on the expansion of British colonisation in Africa in a way that makes the people affected by it the focus of the enquiry.

This is due to gaps in my knowledge, but also to the ways in which a large number of questions on the exam papers are framed. They tend to approach this topic by asking students to weigh up the importance of different motivations for British colonisation in the African continent.

How can you tell whether it is possible to reframe elements of your GCSE and A-level courses in order to allow for deep representation? In my work I have been guided by the following key questions.

Are there ways of telling a story about the events you need to cover that will allow you to place underrepresented stories at the centre of the enquiry?

Will this new framing allow students to engage with important historical questions about the period?

Might doing this serve to enhance your students’ understanding of the periods and themes you are covering?

At A-level there is one area where we have greater liberty to shape the curriculum.

The NEA element set out by my exam board only requires us to ensure that students are covering approximately 100 years of history and that there is not significant overlap with the content they are covering in their other courses.

The sheer number of students taking our courses precludes us from offering a free choice of topics.

So this year we have decided to make a virtue out of necessity and have designed an NEA course focused on the experiences of women, the Black British community and the LGBTQ+ community through the 20th Century.

The aim of this course is not only to allow the students to explore the stories of groups underrepresented in the curriculum, but also to engage with elements of the discipline that they would not normally encounter.

Exam specifications still lean heavily on political history, and this in turn affects the kinds of evidence and interpretations that students encounter.

It is our hope that by telling a social history of the 20th Century students will be able to engage with the kinds of evidence preserved by communities, to engage with questions about its preservation and what this tells them about silences in the archive, and to grapple with interpretations made by historians working in sub-disciplines like social and cultural, women’s and queer history.

This brings me to my final point about the importance of representation in this context. We should see our work at Key Stages 4 and 5 as a continuation of the rich and rigorous historical education we can offer our students at Key Stage 3.

Overall, I have found that, while some creative thinking is necessary to navigate the restrictions we have to reckon with at Key Stages 4 and 5, there are still plenty of possibilities to continue to reform our curriculums with representation in mind.

Claire Hollis is Head of History at Reigate College, Surrey.