Tom Pattison, Director of Humanities at Greensward Academy explains, how Peter Frankopan’s The Silk Roads inspired him to create a new scheme of work for his pupils. He discusses the whole process here.

Deciding where to shine the light in history is a challenge and a privilege in equal measure.

All things curriculum have dominated educational discourse over the last couple of years, and as a subject community, we have benefited from exceptional advice and guidance made freely available through numerous sources including the Historical Association (HA), certain blogs and via Twitter.

The fact remains though, that what goes into a school’s curriculum is a decision that ultimately rests with the subject lead.

It carries a responsibility to see the bigger picture and find a way to make it work for their school. Indeed, something Richard Kennett shared in an HA lecture really chimed with me; your curriculum should be bespoke – it should be difficult to deliver your curriculum as effectively in any other school.

It was with this in mind that I set out to navigate a process of translating historical scholarship into classroom teaching.

Genesis

Modern history has always been my thing. Whether flicking through my copy of Modern World History by Ben Walsh in GCSE lessons to learn about Vietnam, leafing through Don Oberdorfer’s The Turn on my lunch break in my gap year or selecting my university degree, my historical hierarchy was clear; Western and European above all else – and this changed very little until well into my thirties.

Ensconced in my cosy 20th Century niche, there had been little to tempt me to delve deeper into what came before.

History Teacher Book Club intervened and inspired me not only to read more history but to pursue a more diverse diet.

A close friend urged me to read ‘the best book he had ever read’ and at the click of a button the journey began.

And what a journey. Describing ‘Silk Roads’ by Peter Frankopan as my ‘time machine’ to my eager Year 7 pupils might be part of my over-theatrical classroom persona, but that does not make it any less accurate.

Places and people which had never before appeared on my radar were now tying together the loose ends of my historical understanding and dramatically shifting my perspective on the past. The book transformed my view of what I think should be taught and why.

Subscribe

Don't miss out - Sign up to receive the latest articles, resources and analysis direct to your inbox

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Through the power of his research and his writing, Peter Frankopan achieved the impressive and unlikely feat of convincing this obstinate practitioner to question the truths on which he had long depended.

Not only did I want the students to fall in love with the period but I wanted them to experience it through the power of scholarship as I had.

The Challenge Ahead

The fire had well and truly been lit. Silk Roads would feature on my revamped curriculum. However, optimistic enthusiasm needs countering with realistic logistics.

This was new territory. Periods taught in my classroom throughout my career were familiar and abundantly well resourced. Genning up on Nazi Germany, Norman England or the Industrial Revolution means you are spoilt for choice.

Silk Roads was different; I had one hefty tome of scholarship and precious little else.

A single historian and a single book would be too narrow a prism through which to view the period and just not enough on which to base an entire scheme of learning.

Building the knowledge base

My process for building my knowledge and understanding was simple. In reading Frankopan, I used the highlights and notes function on my Kindle extensively.

This meant my key annotations were compiled automatically, which made it easy to return to these anytime I wanted.

My approach was to print off the many pages of notes and then annotate and highlight into themes.

The next and most enjoyable stage was to read around this new topic. So, I looked at A History of the World in 100 Objects book and podcast series. I listened to BBC In Our Time episodes such as The Silk Road, mined the History Today Archive for gems like William Willets and Evelyn Welch.

And, of course, an appeal via Twitter meant that my cup overfloweth in no time. I again printed off the articles for annotation or made notes while listening to the podcasts.

Above all, the most valuable experience was using half term to visit the British Museum. There is nothing like being amongst the physical evidence of the past.

My initial enquiry question was “How did the Silk Roads shape our world?”. I broke it down into smaller enquiries based on my research.

I also decided to create two separate schemes of learning to be delivered in term one of Year 7 and Year 8. Threading a link between the two enquiries would help the students to see continuity across the key stage.

The rationale behind my sequencing was to start global before sharpening the historical lens towards regional, national and local history.

Planning to teach

A scheme of learning will succeed or fail partly based on the effectiveness of the planning stage of the process.

Realising this, I worked with members of our team to create a planning structure, which helped to distill my research into a cohesive scheme of learning.

Crucially, the depth of the document makes it a record of not only the enquiries to deliver but the thinking behind them which has proven to be invaluable to those delivering the content.

As an example; the first requirement is to identify how the scheme relates to prior and subsequent learning.

Further, I felt it was important to identify a number of knowledge ‘take-aways’ for the unit and, additionally, I included specific vocabulary to be explicitly taught to the students to proactively tackle literacy barriers to historical understanding.

Uppermost in my thoughts was guarding against the ‘dumbing down’ techniques so prevalent in my early career and instead build in access routes for all learners.

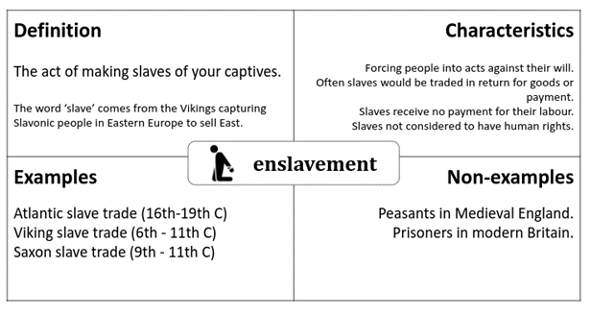

A constant feature of my teaching, Frayer models, are now embedded throughout History teaching at my school.

These simple graphic organisers require students to define target vocabulary and apply their knowledge by generating examples and non-examples, giving characteristics, and/or drawing a picture to illustrate the meaning of the word.

An enslavement Frayer Model (Fig.1) is included here.

Figure 1:

Roughly 20 years ago Christine Counsell discussed how substantive knowledge could be divided into ‘residue’ and ‘fingertip knowledge’.

Residue knowledge is the knowledge left behind after the SOW/L has been taught. Residue knowledge is the precise knowledge needed to access a particular enquiry.

This has sometimes been called Hinterland Knowledge. To help the other teachers in my department teach this unit I highlighted this:

In much the same vein, flagging up misconceptions (Fig.2) in advance allows the teacher to pre-empt or disabuse these commonly formed fallacies.

Figure 2: Misconceptions:

- Western Europe is the centre of the world.

- Rome was the capital of the Roman Empire.

- Women were treated as second class citizens in the Ancient World.

- Christianity is European.

- Europeans successfully resisted the Moguls.

- Europe has always been superior intellectually to the East.

- Islam, Christianity and Judaism have always been rivals.

- Globalisation is a modern invention.

High Challenge, High Access

Widespread belief that reading scholarship is beyond the capabilities of many students deters some educators from considering it. I wanted to challenge this head on.

In my opinion, Simon Beale made this task far more straightforward when he composed and shared his approach to ‘guided reading’. It is a deceptively simple method resulting in very positive outcomes.

The addition of a glossary of tricky words to be discussed prior to reading reduced student apprehension over tackling a ‘grown up’ text and bred confidence.

Place and period

To help students understand the past, it is a good idea to provide them with a sense of place and a sense of period.

Therefore, I used timelines and maps at every opportunity. The very first enquiry centred on a comparison between contemporary and ancient maps.

Frankopan very helpfully released a superb illustrated version of the book with the aim of making it more accessible to school age children.

Consistency

I was keen for teachers to feel comfortable to teach in their own preferred style, yet felt acutely aware that the needed to be a level of consistency.

Booklets were my chosen compromise. Creating a bespoke booklet containing the key content, guided reading and suggested activities would identify the content to be shared without reducing my team to automatons.

Future reflection on what to keep, what to tweak and what to abandon would be informed by shared experiences. Both booklet and scheme were to be considered working documents.

A further benefit of the booklet approach was it facilitated transition from PowerPoint domination to a visualiser supported, live modelling approach.

Reflection – Listen more

Translating scholarship to a scheme of learning for Key Stage 3 students was ambitious.

Reflection should be an ongoing process and although the scheme of learning has a long way to go until I can be truly happy with it, already the lessons learned from the first run through of teaching in 2019 led to a markedly improved 2020 version.

The most significant change that resulted from our reflections was adjusting the overall enquiry question.

Asking students to determine how the Silk Roads shaped ‘our world’ was too vague and encouraged generalised judgments centred on the present rather than the period of study.

Switching to shaped ‘the world’ placed the emphasis on consequences within the period of study and raised the level of historical dialogue within the classroom as a result.

In addition, by refocusing the smaller enquiries to foreground different methods of investigating the past it was possible to explicitly introduce the students to the discipline of history.

Distinguishing between craft and content is a minefield as proven by my chequered past of well-meaning but flawed What is History? units.

It was hoped that through a growing familiarity with both text and historian, students would be better placed to appreciate the process by which interpretations of the past are created.

The overall enquiry question was:

How can we learn about a period thousands of years ago and thousands of miles away? This was planned to last for 6 lessons.

The smaller enquiries that made this up were:

What can we learn from a map about how the world has changed?

What can we learn from an historian about the Silk Roads?

What can we learn from art and artefacts about the Silk Roads?

I admit to being apprehensive about laying open my precious scheme and booklet to critique but the pruning process proved an unexpectedly enjoyable experience.

Collaboration over what to remove as well as what to keep in was essential.

Easing the cognitive overload of the sheer volume of resources I included in the first booklet improved learning outcomes. Trusting in my team and listening to their recommendations taught me much about effective planning and leadership.

Keep it simple

Homework and assessment was overlooked in the first version. It became apparent in the teaching that opportunities for gauging students’ progress and enriching their sense of period were not being made enough of.

The result was an overhaul of both homework and assessment influenced by Tom Sherrington’s approach.

In came a streamlined version in the shape of two models.

Homework A is a fortnightly MCQ quiz to establish what the students could recall, whilst Homework B embraces the Meanwhile Elsewhere format with more time allowed for completion.

Directing students to explore a concurrent event to the one under study in lesson has been truly revelatory in expanding the historical horizons of our students.

I also revamped the booklets with follow up activities to the guided reading tasks – which felt like the missing piece of the jigsaw.

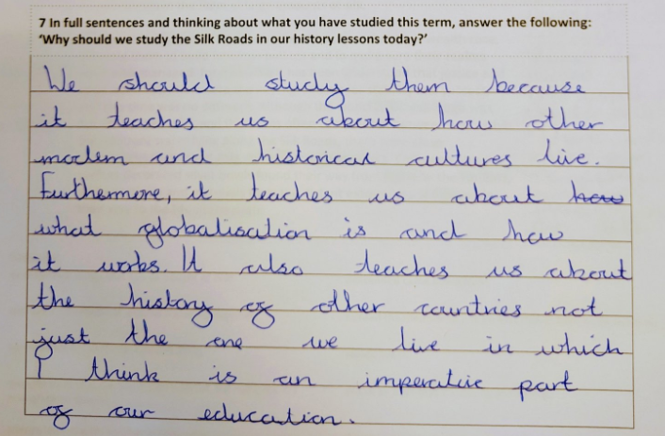

Improvements in students’ historical writing have been clear to see and it is hugely exciting to see the marriage of scholarship and literacy.

The pay off

Celebrating student success should be a regular and prominent feature of every teachers’ practice. When we raise the bar, more often than not students surpass the high expectations we have for them.

Fig. 3

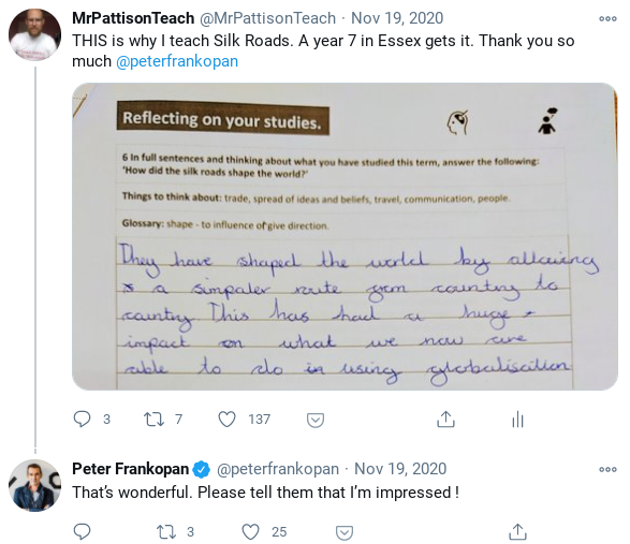

It was fitting then that when I tweeted out my pride in one student’s reflection on studying Silk Roads it was Professor Frankopan himself who responded.

To have started off reading a book, felt compelled to teach it and for it to come full circle like this was a very satisfying moment.

Fig 4.

Best of all though was the reaction of the students when I shared it with my classes; you could see them swell up with pride that their efforts had garnered praise from the foremost expert in the world on the period. In a tough old year it was comfortably the highlight.

Ambitious schemes of learning challenge and bring the best out of students.

What we choose to teach must reflect the discussions and debates taking place between fully fledged historians if we are to keep the subject relevant and stimulating.

I firmly believe there can be no more effective way of doing so than acting as the conduit between historian and history student.

Tom Pattison is Director of Humanities at Greensward Academy, Essex.