Rachel Ball, Assistant Principal at Co-op Academy Walkden, gives a detailed insight into how she has changed her approaches to revision. She provides practical take-away ideas to apply to your own classes.

We know that the 2021 exam season will look very different to usual. However, the principles of good revision are universal.

This article was written with Year 11 revision in mind, but the ideas and strategies can be applied to any group of students who will be sitting assessments.

Have I been doing it all wrong?

It hit me a few months ago that I may have been doing GCSE revision lessons all wrong. In a school with (until this year) a three-year Key Stage Four, we have often found ourselves at the end of the course, around Christmas, ready to start revision.

I would then usually start the process of re-teaching the key topics ready for the exams.

I might also have asked the students to ‘RAG rate’ their confidence with topics to guide me about what I should focus on over the next few months. At the same time I would tell students they should also be revising independently at home – without showing them how to!

The Rationale for change: What some scholarship taught me

The first aspect that has had an impact on the way I deliver revision lessons is the wealth of research on retrieval practice and the “testing effect”.

There has been an increased interest in retrieval practice in England recently.

In her book Retrieval Practice, Kate Jones explains that: “The retrieval process cements the information in the long-term memory, which should enable that information to be easier to retrieve in the future.

“Retrieval practice focuses on recalling information from memory as a powerful learning tool, not an assessment tool.

“Therefore, is it regarded as essential classroom practice to support learning with the regular practice of retrieval.”

This is important to help cement substantive knowledge into our pupils’ minds. However, it is important to remember that history teaching is also made up of disciplinary knowledge.

Teaching history via second order concepts is as important as remembering information. There is a wealth of scholarship supporting this view. Peter Lee pointed this out in his seminal work here.

Further, the Roediger and Karpicke study of 2006 (Psychological Science) outlined in The Science of Learning by Bradley Busch and Edward Watson tells us that “practicing the ability to recall information improves our ability to do so”, even though it isn’t necessarily the strategy students would naturally choose to use.

In addition, I have recently read Zoe and Mark Enser’s book Fiorella and Mayer’s Generative Learning in Action.

Generative learning is explained by Mayer in the book’s foreword as “making sense of our experience by testing it against what we already know” and its heart is the SOI model, where students select, organise (e.g. turn knowledge into a new form or structure) and integrate their knowledge to existing schema.

This is really interesting as, surprisingly, it seems to agree with constructivist approaches to learning.

The idea that students need to do something with their knowledge in order to process it and build schema has again given me lots of food for thought in the planning of all lessons, but specifically revision lessons.

Retrieval practice seems to be becoming much more embedded in schools now and certainly in my school, it has fundamentally changed our approach to all lessons – and therefore to revision lessons as well.

However, just focusing on retrieval practice isn’t enough. We should also focus on ensuring pupils are motivated.

How have my revision lessons changed? – The principles

I no longer ‘start’ revision when the course ends. Embedding retrieval practice into my curriculum has shown me that retrieval as revision should on-going, and I need to model this, in order to facilitate the movement of substantive knowledge into the long-term memory.

At my school every lesson starts with some form of retrieval, and we regularly test substantive knowledge not just from last lesson or recent topics, but from earlier in the course (“spaced” or “distributed practice”).

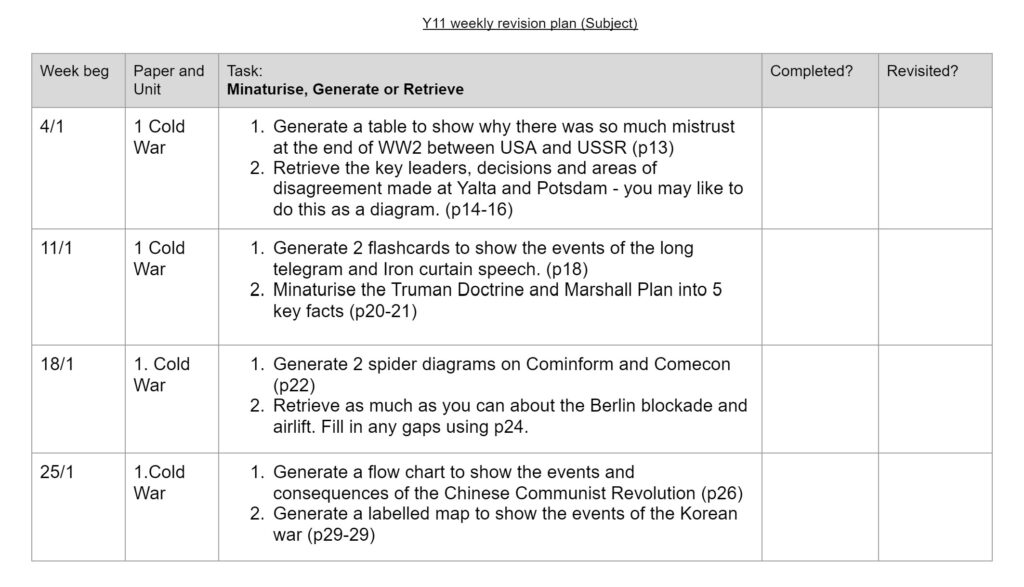

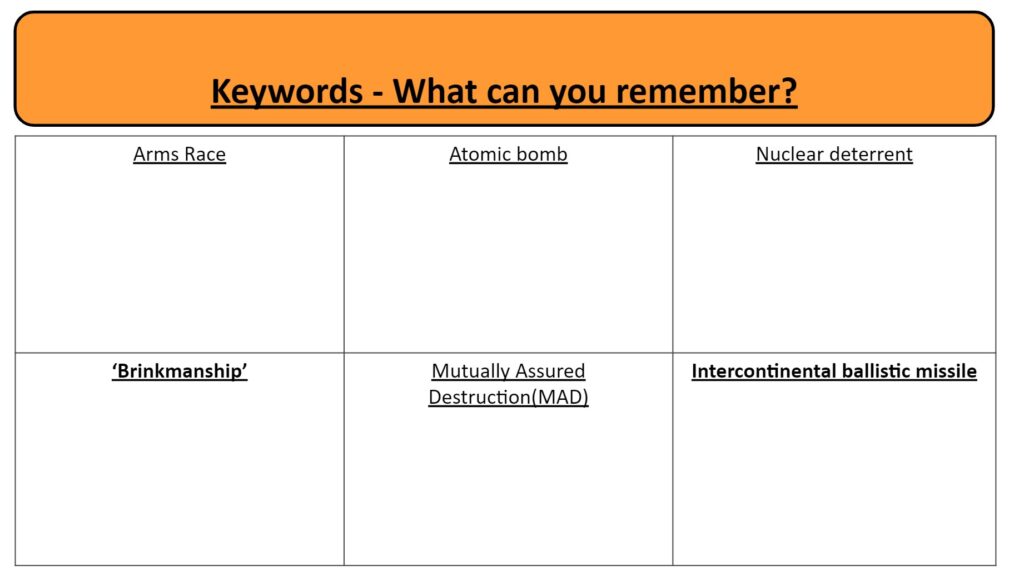

Homework consists of retrieval grids such as the one below, where students fill in what they know from memory, add to it what they had to look up and then the next lesson they sit a ‘low-stakes’ quiz based on the content of the homework.

Elaborative questioning then takes place: Which question did you find hardest? How could you remember this fact? Why? Where does this topic link to other parts of the course? Where are your biggest gaps and which topics do you need to revisit?

Over time, students’ confidence increases, and they see revision as a constant process, rather than cramming before the exams. It also gives them a really workable format to use at home again and again.

I always encourage them to have another go at the grid at home after a gap to see if they remember more!

By completing revision in this way throughout the course, not only does it require no marking, it ditches this approach of revision being something we do just before an assessment and moves students away from the cramming approach.

I explicitly discuss how to revise with my students on a regular basis because I know that for most students they don’t know how to do this effectively.

I firmly believe that students, unless actively encouraged, will not choose the right methods of revision.

We tend to do what is easiest, and to students this is re-reading, highlighting or looking over material.

So, whenever we take part in a retrieval activity like the revision clock or filling in a partly blanked knowledge organiser, I will make a point of saying how this can be used as part of their independent revision.

The principles of good revision, moving away from highlighting and re-reading, are something which are explicitly talked about in lessons right through from Key Stage Three.

Therefore, very few students in my Year 11 would dare to claim that they do not know how to revise.

In addition, I openly talk to my students about how revision will not feel comfortable.

Whilst we do retrieval practice activities I narrate to students so that they may feel out of their comfort zone and relate it to Bjork’s work on “Desirable Difficulties”.

Bjork’s work details the concept that introducing more challenging activities into the learning process can greatly improve the retention of material in the long-term, and that the tendency by teachers to make activities easier is actually counter-productive.

In the 1980s and 1990s, such task were described by HMIs as ‘satisfyingly difficult.’

For students, the learning should and will feel hard, but the evidence suggests this leads to more efficient learning – it’s about finding that sweet spot of challenge.

I no longer ask students to RAG rate their confidence on particular aspects of the specification and concentrate on parts they have low confidence on in my revision lessons. I’ve learnt that much of the time students don’t actually know what they don’t know.

Daniel Willingham’s article here explains this in depth, suggesting that familiarity and partial access to the material might give some students the impression that they don’t need more work on a certain topic when in fact they do.

Willingham concludes: “In particular, teachers can help students test their own knowledge in ways that provide more accurate assessments of what they really know — which enables students to better judge when they have mastered material and when (and where) more work is required.”

Instead I identify gaps through assessments, feedback from low-stakes quizzing and my experience of the parts of the course that are traditionally more difficult.

The structure of my revision lessons

Every revision lesson begins with retrieval. I use a mixture of simple quizzes and retrieval which requires some more challenging thinking. You can find some ideas on my “History How To” on Retrieval here hosted on Greg Thornton’s website.

You can also read about some ideas for making retrieval more challenging, such as incorporating The Writing Revolution or addressing misconceptions in my blogpost here.

I also think carefully about what I include in my retrieval and make sure it is linked to the lesson wherever possible. For example, when students encounter ‘laissez faire’ in the AQA Britain: Health and the People thematic study, I could make a link to laissez faire as a policy in 1920s America.

Here are some examples of this revision strategy in action. During remote learning, Google Forms as quizzes have been brilliant for this, enabling me to see where misconceptions and errors lie which I might not otherwise be able to see.

Figure 2:

I then share the big picture for the lesson and how it relates to the whole unit and the course.

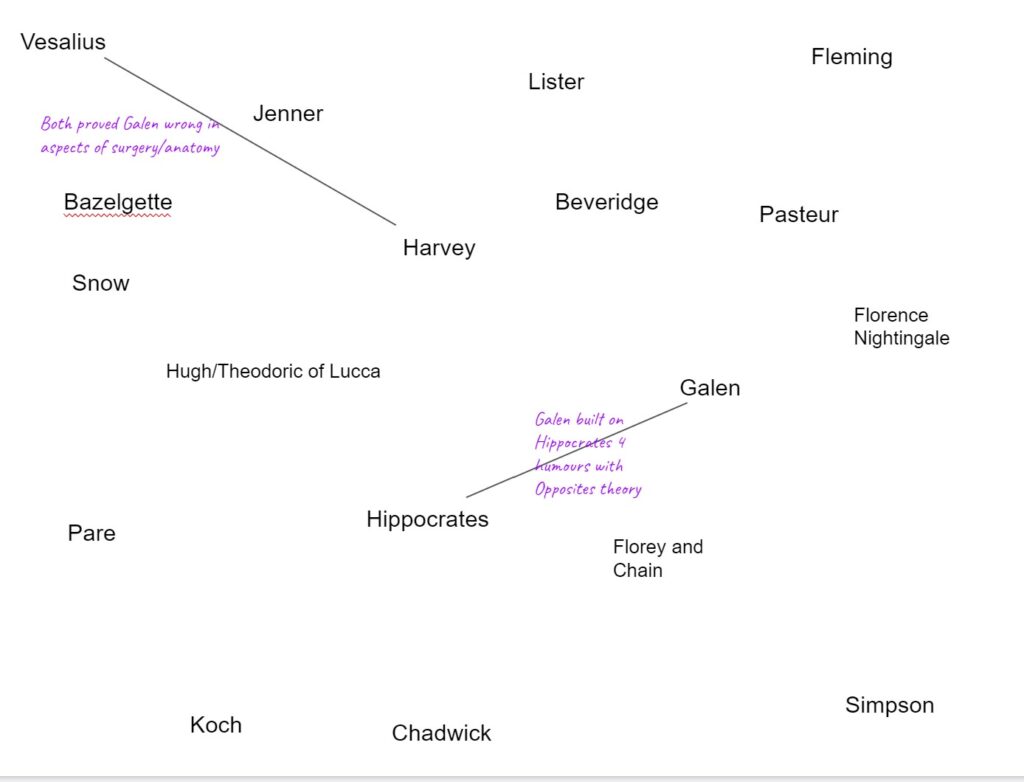

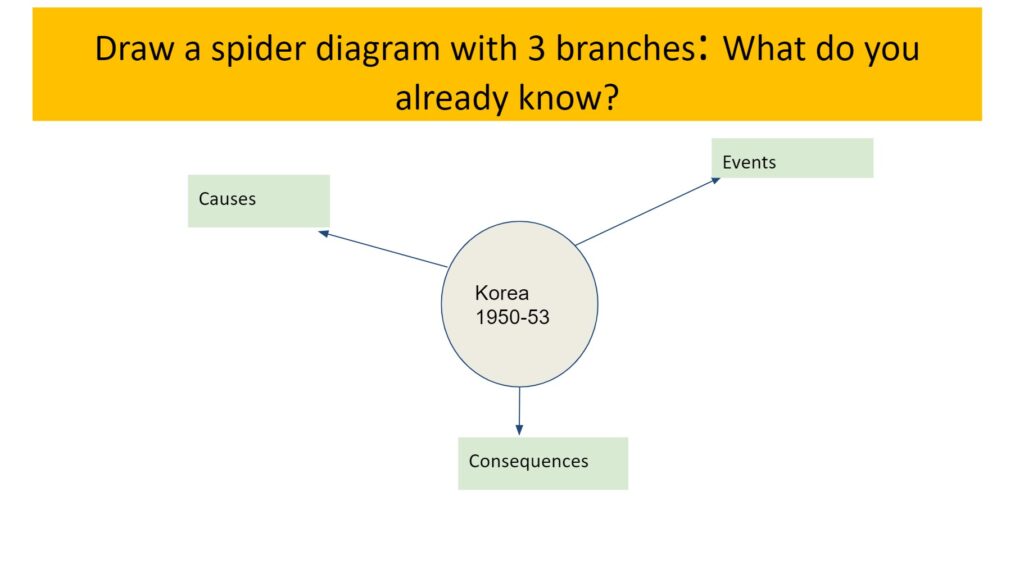

At the beginning and ends of each topic I will also use mind maps or timelines to help students understand how the different parts of the content interrelate.

Too often we forget to share this big picture and assume students just get it. If we want them to become historically literate they need to develop a ‘big picture framework’ of the past.

So, they need to see how what they are studying today fits into this big picture by making it visible.

For example, when starting revision on the Cold War in the 1940’s I could start by giving students a blank timeline and asking them to add as many of the important events as they can remember, or present them with a concept map to show how the event covered in the revision lesson may be linked to other events in the unit.

The third element of the revision process is where I have made the biggest change to my practice. At this point I would usually have re-taught the revision topic, trying to cram in as much information as possible.

For example, if the Allied war conferences of 1945 were the subject of the revision lesson I would simply have retold the story of the main decisions made at Yalta and Potsdam with discussion about the tensions and the repercussions for the Cold War.

Now I always see what the students know first. For example, I might give students a blank table with columns for the names and dates for each of the conferences.

This would include space to write down the leaders involved and the key decisions and tensions, giving them time to fill in as much as they can from memory.

I can then use interrogative questioning to find out where the real gaps are (rather than the imagined gaps) and re-teach those misconceptions or gaps in learning.

I could then easily repeat the exercise at a later date as a stand-alone activity to see if their retention on the subject has improved.

At this point I would now encourage students to do something generative with their learning and there are a few key strategies which have been most beneficial to me in my classroom.

The first is summarising – asking students to reduce the key learning points down into three bullet points or three key questions, for example. I’ve found Cornell notes really useful here.

Another method I use frequently is ‘mind mapping’. Students could start with a blank mind map for the retrieval section of the lesson, then add to it with any gaps in their learning, followed up by a task to show links between different aspects. For example, a mind map with the three key Renaissance individuals of Vesalius, Pare and Harvey could then be followed up by asking students to egxplain any similarities between their work (also preparing them for the comparison exam question).

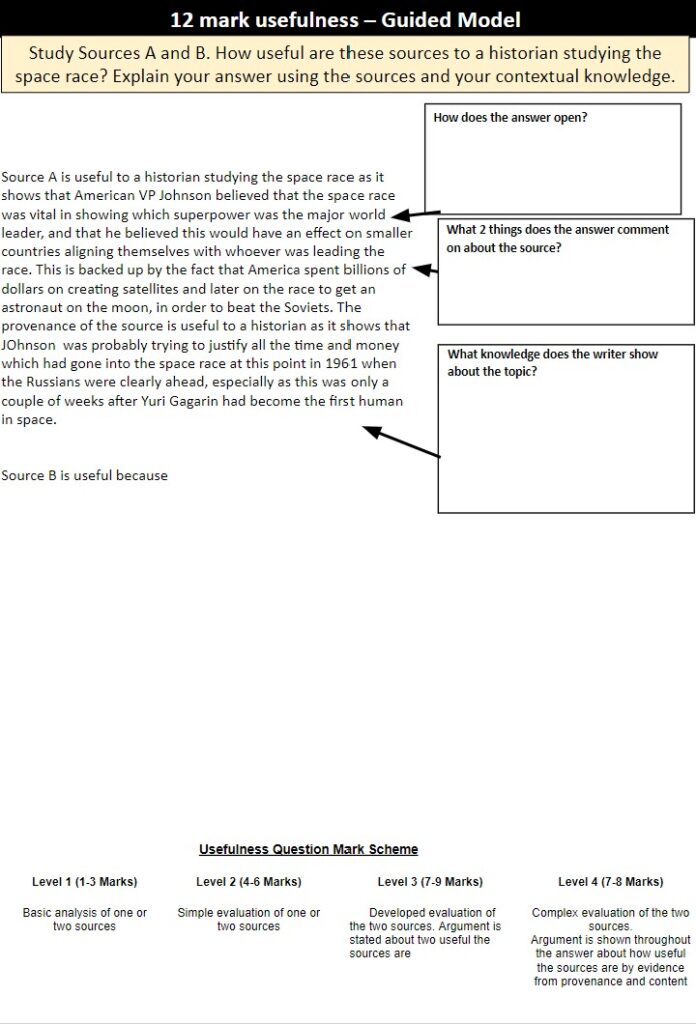

The next section of the revision process would involve some exam practice application.

In the past, I would always have asked students to do this independently, but I now recognise that even at the stage of revision lessons in Year 11, students still need some scaffolding to start.

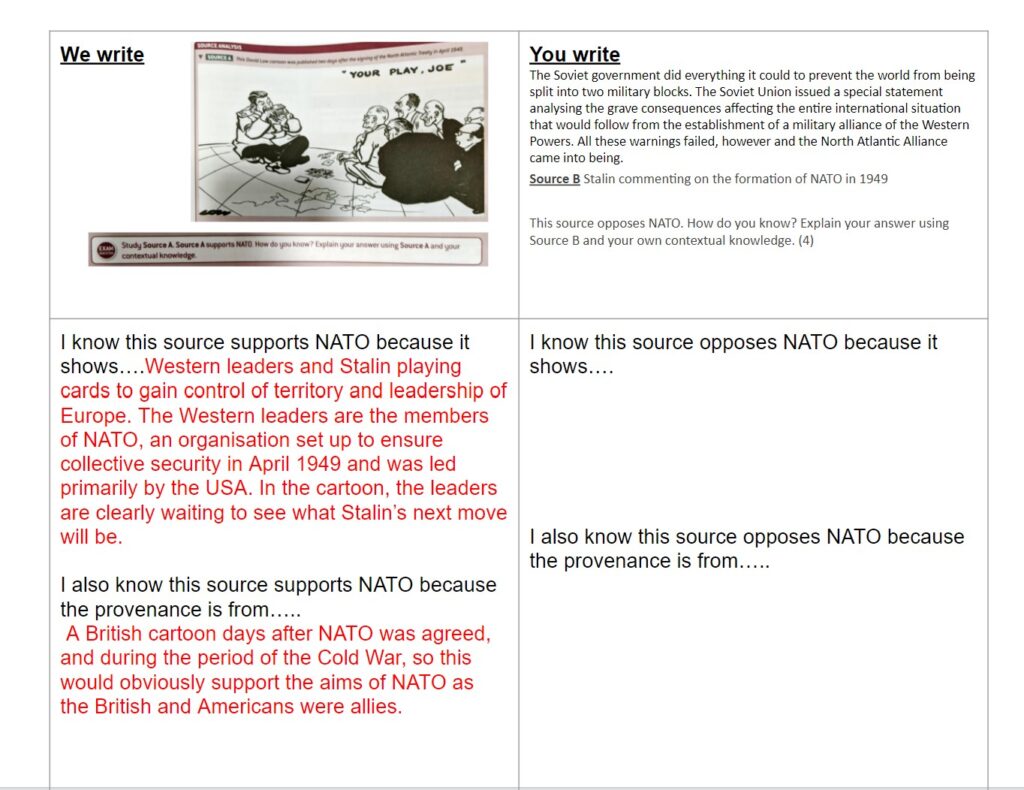

The best way I’ve found to do this is the I do, We do, You do approach.. This approach of ‘backwards fading’ has revolutionised my teaching. Modelling like this is highlighted in X article on visualisers link to the visualisers article Staffs!

Practically, my revision lessons might not always be as simple as I do, We do, You do – but essentially I start with showing students what success looks like.

We’ll annotate and break down the question together, then I’ll model my thinking and planning process before presenting them with a good answer.

We’ll discuss how the answer is structured, the effective use of vocabulary, the application of provenance and content and so on. I never just get students to look at the answer, but to actively engage with it, even asking what elements they would “steal” if they had a similar question.

We then engage in one or two answers or parts of answers as a class, where I will ask them to guide me with what I write, usually under a visualiser.

This works well alongside ‘cold call’, asking particular students to suggest what might come next, pushing them for correct vocabulary and impressive sentences. Finally, and only when I feel students are confident about the question, will I ask for independent work.

Gradually of course the students become more independent and the ‘I do’s’ are less needed, but it’s a great way of scaffolding, showing students they can be successful and ultimately building motivation.

The future

I now feel that my revisions lessons have been informed by recent scholarship and I feel that my students are better prepared for the increased demands of recalling content and applying it to questions in the present GCSE exams.

My emphasis has moved away from trying to cram in re-teaching everything, to a focus on retrieval throughout the course and then application of knowledge to exam questions. I feel this is having a positive effect, not only on the outcomes of my students but on their confidence and motivation as well.

In Summary

-

Regular, spaced retrieval is far better than rushing through a course to revise substantive content at the end.

-

When revising, find out what students know first – don’t just reteach the course

-

Give students a chance to be generative with their knowledge

-

Embed regular modelling into exam practice

Rachel Ball is Assistant Principal of Teaching and Learning and History Teacher at Co-op Academy Walkden, a large 11-16 school in Salford.