In November 2022 I enjoyed reading Tom Haward’s good ideas on using visual sources in the classroom.

It made me think about a question I am often asked regarding the use of cartoons in examination papers.

Are they too complex for students to respond to under time pressure in the exam hall?

It is a fair point. Examiners often try to deal with the issue by choosing a cartoon that is likely to be familiar – one that is in the textbooks or freely available.

So that means it is makes sense to spend some time in the classroom deconstructing cartoons.

In setting evidence questions it is good practice to use a familiar source with an unfamiliar one.

It makes an effective test of students’ knowledge and understanding if they can reconcile the familiar with an unfamiliar source or text.

How can we help students to deal more effectively with cartoons?

The first stage is, obviously, to make them used to identifying the surface features of a cartoon.

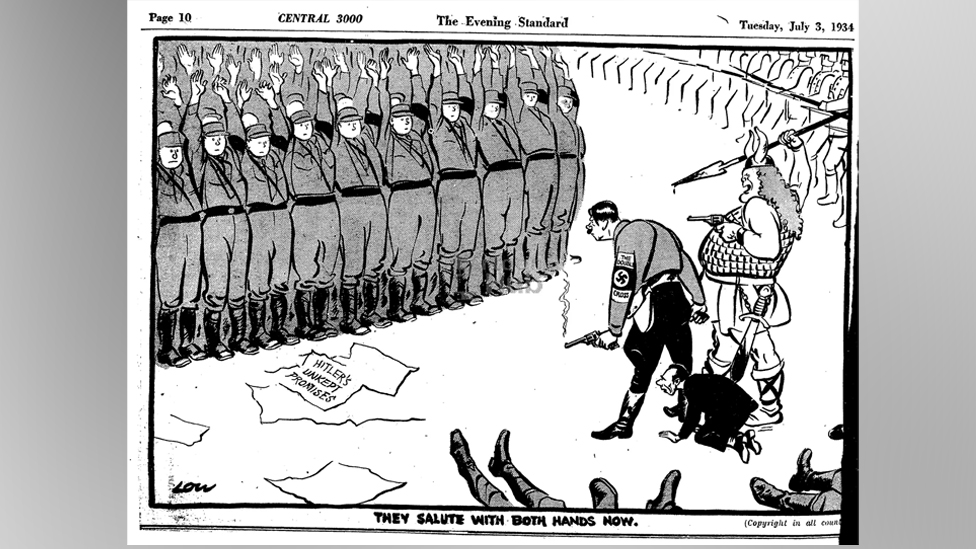

It might help if we try to model the process. We can use the well-known, “They salute with both hands now” or “Double Cross” cartoon about the Night of the Long Knives created by David Low and published in the Daily Herald on 3 July 1934.

This is a complex cartoon; there are many surface features or elements in it to be identified.

There is a group of men with their arms in the air – the SA or Brown shirts. Hitler is the central figure holding the gun with a swastika armband.

To his right, armed with spear and gun, dressed as a Viking, is Goering, and on all fours, observing the SA through Hitler’s legs, is Joseph Goebbels.

There are three other elements to the cartoon – the outlines of advancing armed men, the legs of murdered Nazis, and the sheets of paper strewn across the floor.

So far, we have done nothing more than describe what we can see.

This is a simple level of visual literacy, like the initial reading of a text.

Stopping here will usually be rewarded at a lower level in a mark scheme.

At this point we need to know what to do with the familiarity we have gained.

Firstly, we should think what we know about the event, and secondly, look at the question.

Students do need to know something about the people or the event in the cartoon.

So asking themselves what they know about the people or event is the next step. To make progress in dealing with the cartoon students must use their own knowledge and try to relate the content of the cartoon to their knowledge of its context.

We have already begun to do that by identifying the Brownshirts, Hitler, Goering, and Goebbels.

This cartoon can be understood as a straightforward narrative of what happened on the Night of the Long Knives.

According to the cartoon, it is reasonable to conclude, at a basic level, that ‘Hitler shot some people.’

Some questions on examination papers that use cartoons are simple and straightforward.

Essentially, they are asking about the message or point of the cartoon, and ask students if they can discern the message and relate it to their knowledge of the historical context.

In fact in some older examination papers, that might even have been the format of the question ie to ask about the message of the cartoon or source.

However, now the most common type of question used in examination papers is one which asks about the usefulness of the sources.

In these questions the usefulness of the source is often related to the message as it depends on who is sending it and the audience it is intended for.

Without some teacher guidance and rehearsal, it is a big leap in the exam room for students to understand the message of the source.

How can we help students in the classroom to deconstruct cartoons, relate them to what they know, and to develop contextual inferences?

To develop understanding we must make students ask questions of what they have previously identified.

Some students will naturally ask questions about visual sources.

Their curiosity will want to know why the artist has portrayed something in a particular way.

For other students it is a habit of mind that we can encourage which, hopefully, will lead them to make relevant inferences.

Considering the identified elements of our cartoon, using what they know, we should ask students to come up with further questions (and answers).

So, for example, who are the shadowy figures in the top right-hand corner – perhaps the army or are they the SS?

How are Hitler, Goering, and Goebbels are portrayed? Why? What do the words on the armband mean? What are the torn-up pieces of paper lying on the floor? What do we make of the title to the cartoon -They salute with both hands now?

How can we help them succeed in the exam hall?

In the classroom, questions like these can lead the students to relate their knowledge of the event to the content of the cartoon and gain a deeper understanding. Many teachers use a model or device like that outlined by Claire Riley’s article in Teaching History, 97, (1999)

But in the exam room students need to be quicker and sharper.

So, perhaps a reductive tactic might help. For the time being, let us ask students to identify the two, and only two, main visual elements in any cartoon.

In the classroom posing the question, Which are the two main elements of the image? should provoke a discussion, and to lead to some useful understanding.

Students should be mindful that little if anything in a cartoon is wasted.

The cartoonist does not have time or ink to waste. The essence of a cartoon is distillation and simplicity.

Yet in that simplicity, ironically, lies the complexity we mentioned at the start and which it is so hard for students to unlock in the exam room.

Most cartoons communicate a point using the interaction of two, or three, elements.

The sine qua non tactic – asking students, which are the two main elements of the cartoon without which they think there would be no message or point to the cartoon, will help them.

Suggest the students to put their hand over the Brownshirts in the image, if what they can see now was all that was there, would the cartoon make any sense?

Similarly, if you put your hand over Hitler, Goering, and Goebbels, would the cartoon be understandable?

In this way we are trying to identify the key elements in the cartoon.

Don’t forget the caption

You will have realised that with the cartoon we are considering, and with most cartoons, understanding the ‘message’ depends on a third element.

This is the caption or title. It links the two main parts of the image.

Some students will grasp the concept easily of a cartoon having a message.

Others may find it helpful to think about a different question.

The cartoonist wants the viewer to think of something, to understand something, and to get a message after seeing the cartoon.

The cartoonist wants to criticise, confirm, pose a question, or say something about an event. What is it here?

The question then, for the student is, What am I meant to think, having seen this?

Focus on those two main elements previously identified, with, if it has one, the title or caption of the cartoon.

Can they put them together and write about the relationship or interaction between them or consider each of the key elements separately?

In doing this they may be helped to understand the point of the cartoon or its message.

Given that cartoons can be complex, students should be reassured that there is often not just one message and there may be different ways to express it.

We might infer that Hitler is a ruthless, has complete power, or Hitler will stop at nothing even killing those who supported him.

And of the SA – they are now docile and obedient, and remembering the title, displaying a traditional sign of surrender.

You could try this approach on some other cartoons and see if helps.

Sometimes using a copy of the cartoon, ringing the two main elements, then with the title, in a triangular approach, students can focus on what they should be thinking and writing about.

The importance of newspapers

In History exams students are likely to be presented with cartoons that have been published in newspapers.

Examiners often comment about how naïve some students seem to be about newspapers as media and the dynamics of the newspaper business.

Some students seem to think that newspapers only make money from being sold.

They rarely understand about the profits made from newspaper advertisements.

In most successful relationships between a producer and a consumer, the producer understands the consumer.

The proprietors or editors of newspapers exhaustively research the values and interests of their readerships.

It is an old debate about whether newspapers follow or lead opinion, and of course, they do both.

But if newspaper editors and journalists fail to get the mix of opinions and information right, then people will stop buying the newspaper because it does not interest them or resonate with their values.

However, crucially, newspapers also want to make money by delivering a known audience to the advertisers of products.

This applies to the cartoonists who must create cartoons that appeal to or interest the newspaper’s readers and if they fail in this, the newspaper will stop using them.

This understanding of the newspaper business, and the cartoons in them, is often absent from students’ answers.

In short, cartoons will express opinions and views about people and events that are relevant, contemporary, and likely to be endorsed by readers of the newspaper.

And remember the role of the historian who wants to discover the truth

Newspaper cartoons in exams will usually focus on an event, or the government, or a country and its actions.

So what do we make of the question that asks about the usefulness of a cartoon?

There is an ingredient in this type of question which may be explicit but is always implicit. That ingredient is the historian.

At GCSE level, it is enough to understand that the historian is interested in the truth of the event or period.

The historian will have a particular line of enquiry or area of interest. It is also usual that the question will suggest the historian’s particular line of enquiry or interest.

The historian will be keen to reflect a balanced range of opinions or ideas from the time about the events or people they study.

The source is evaluated for what it might contribute to that line of enquiry.

In our cartoon, for example, the line of enquiry in the question might be about a historian who is interested in Hitler’s dictatorship, or power by 1934.

Therefore it may help students to ask a simple question, Is the cartoon critical or supportive?

An alternative question might be, Whose side is the cartoonist on?

If the students have grasped the message of the cartoon by focusing on the interaction between two key elements, and the title, then explaining why the way in which the cartoon is either critical or supportive, it may prompt them to explain its usefulness for a particular line of enquiry.

- Tags: Cartoons, GCSE, GCSE teaching, Modelling, Source Analysis