For many beginning and early career history teachers (ECTs), the key draw into the teaching profession is their love of history– after all, unlike many of their contemporaries training to teach other subjects, they do not currently receive a bursary to train.

Why then, once they get into the classroom, does the history sometimes get overlooked in favour of generic teaching strategies?

And how can mentors put the focus back on the historical learning happening – or not happening – in classrooms?

Genericism and the experience of beginning and early career teachers

In recent years, efforts have been made to strengthen Initial Teacher Training (ITT) and the experience of early career teachers through the introduction of the Initial Teacher Training Core Content Framework (CCF) and the Early Career Framework (ECF).

These frameworks define the minimum entitlement beginning teachers can expect from the curriculum and the mentoring they receive as they enter the profession.

Both frameworks place “strong emphasis on the need for training to be subject and phase specific”, however, this is not the reality for many ECTs.

In April 2022, Teacher Tapp reported that 60% of ECT mentors felt the ECF programme was not subject/ phase specific enough.

Meanwhile a 2023 Teacher Tapp and Gatsby Foundation report revealed that, in the first 18 months of the ECF’s implementation, 27% of humanities ECTs surveyed did not have a subject-specific mentor and only 9% of Secondary ECTs felt the external training had been specialised to their subject/phase.

At the time of writing, the signs are that the roll out of the ECF has been a missed opportunity for the subject-specific professional development of beginning teachers. However, there are other potential reasons for a lack of subject-specific development.

For example, whole-school CPD is often understandably focused on generic strategies that can be rolled out across the whole school.

Similarly, generic core-practices are easier to spot happening during observations, especially when those observations are undertaken by teachers from outside the subject specialism being observed.

Taking a subject-specific approach to lesson observation requires a deep understanding of the subject. It is also a skill very few of us have been trained in directly.

How can we forefront historical learning during lesson observations?

Taking a subject-specific approach to mentoring is crucial.

We know that history is an absolute gem of a subject (who would want to teach anything else?) and that subject specific professional development works.

Lesson observations (and the conversations that follow) have the potential to be one important aspect of this.

Therefore, how can mentors help their mentees focus on the historical learning in their classroom?

Avoiding the observation trap. Focusing on historical thinking and reasoning

Digging into the historical learning that is (or is not) happening in an observed lesson is much more difficult than identifying generic features of practice for development.

In our roles as ITE tutors we frequently see post-lesson observation targets focused on refining core practices.

For example, where questioning has been identified as an area for development, targets are likely to include instructions to “up the ratio of questioning”, “deploy longer wait times” or “use cold calling techniques”.

While these targets are specific and precise, and no doubt mentees will need to work on these aspects of their practice, such targets will not help a mentee to ask better, more historically focused questions.

No amount of cold calling will help a beginning teacher understand how to plan (and then ask) more historically rigorous and purposeful questions that are linked to the activity or lesson’s historical takeaways.

Beginning teachers need their mentors to avoid this observation trap.

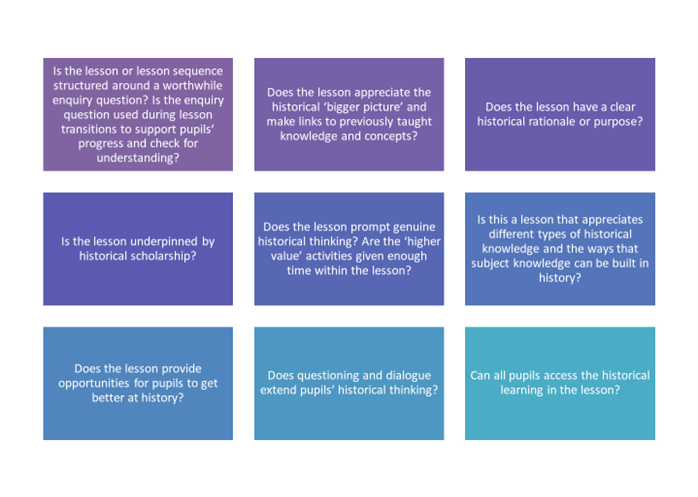

You can read more here. In Mentoring History Teachers in the Secondary School we set out a tool designed to help mentors to forefront pupils’ historical learning during lesson observations.

Designed alongside history mentors, the tool identifies common subject-specific aspects of teaching for beginning teachers to work on.

By using the following questions during observations, mentors are nudged into thinking more deeply about the historical purpose of the lesson.

Additionally, the tool encourages mentors to take a more questioning, dialogic approach in post-lesson conversations and target setting.

The value of taking dialogic approach to subject-specific reflective conversations with your mentee

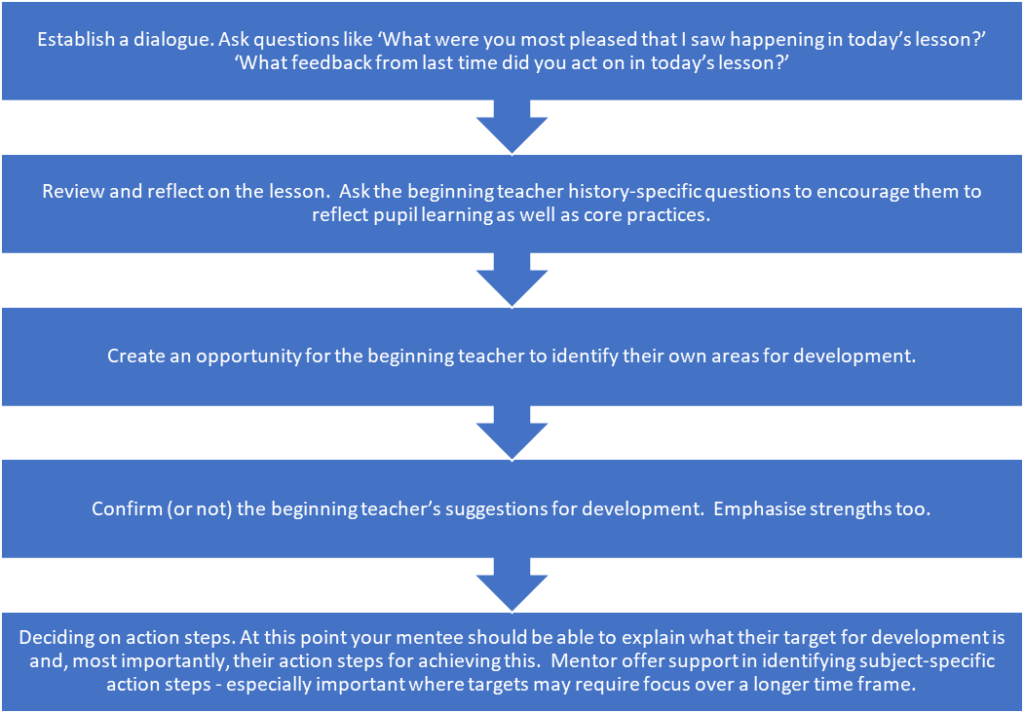

Taking a dialogic approach to reflective mentoring conversations is the perfect forum for subject-specific mentoring practice.

This approach attempts to avoid “judgementoring”, a term devised by Hobson and Malderez, to describe a situation when a mentor is very quick to reveal their own solutions during lesson feedback, providing a laundry list of advice and targets, or providing very strong advice.

Taking a dialogic approach, using questions like those provided in the observation tool, allows mentors to meet their mentee at the point of their own understanding.

It also helps their mentee to develop their own reflective abilities. By prioritising the historical aspects within a lesson, we also enable the beginning teacher to think beyond the performative aspects of their teaching, to consider more deeply how they have supported pupils’ historical learning.

In Chapter 6 of Mentoring History Teachers in the Secondary School we suggest the following structure for successful post-lesson conversations:

Target setting on a continuum

It is also helpful to think of targets on a continuum between hard-edged, specific targets and those that will take more time to work on.

For a beginning teacher, getting better at asking more purposeful questions will show itself more readily (there are opportunities for this every lesson) but getting better at teaching causal reasoning will take much longer, if only because there are fewer occasions to address this target.

It is important to recognise that not all targets can be broken into tidy, action-steps that can be frequently practised.

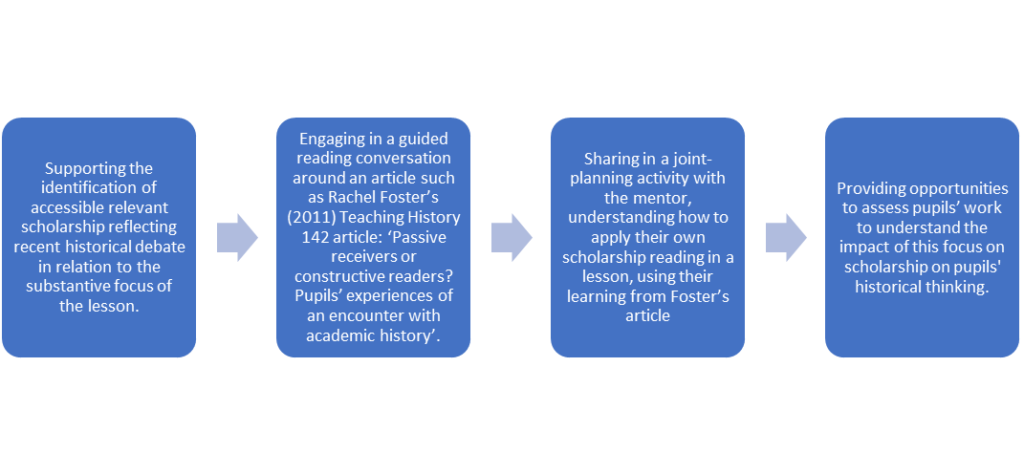

Setting longer-term targets accompanied by reading, observation and collaborative planning is a valuable way of supporting beginning teachers’ professional development in the long term.

For example, a beginning teacher struggling to meaningfully integrate historical scholarship into their lesson, may need action steps applied over a series of weeks, including:

Avoiding genericism in written feedback

Written feedback is important as it is often where targets are formally recorded.

It is always worth removing the word history from the title of written feedback and reflecting on whether it’s possible to tell what subject it relates to.

Written feedback which is totally generic and devoid of history-specific content, can send a message to the beginning teacher that performance matters more than substance or may lead them to see the purpose of history education in solely generic terms, for example to improve literacy rather than to think historically.

Using the history-specific questions set out earlier will help you to set subject-specific targets.

Judicious use of targets is important too, a laundry list of ‘things to do’ is unhelpful and demoralising. Your mentee will also be observed by other members of the history department so, to avoid overloading with generic to do lists, you can support colleagues with their subject-specific feedback by sharing your mentee’s weekly overarching targets with the whole team.

We have visited departments who do this is in all sorts of ways- from a weekly email, to adding these to a whiteboard in the history office, to asking mentees to copy and paste these at the top of observation forms.

Learning together as history teachers

Finally, take a moment to think back to times when you have been observed teaching and the feedback that followed.

Consider who observed you, for example, were they a history-specialist?

Think about how this shaped the feedback you received. Is it possible that we learn more from observing than being observed?

And that this is one of the benefits of being a mentor? This was certainly true of our experience. As you use the subject-specific observation tool, you will inevitably reflect upon the historical thinking that happens in your own classroom.

Observation of other history teachers is really good professional development – make the most of this opportunity, not just for the beginning teacher, but for you too.

Help your mentee to recognise the value these subject-specific reflective conversations have on your own development and help them to value observation.

If you are in charge of their timetable, build in opportunities for observation throughout their ITE year.

The benefits of observation are so much greater when you know what to look for, see Vic’s blog for a list of subject-specific questions to support beginning teachers to spot historical thinking happening.

A love of history has moved so many of us to become history teachers, yet 91% of our ECTs, who are so vital to the profession, say they do not currently receive subject-specific support from their external ECF programme.

Therefore, their main opportunity for meaningful engagement with subject-specific professional development is through their mentors.

That’s quite a responsibility, but it also presents an opening for some of those joyful, curious conversations about historical learning that you probably wouldn’t have with anyone else.

Centring history in our mentoring practice is so important, not only for the quality of historical engagement in our classrooms, but also for the retention of these new teachers – and maybe even their mentors. Why not give it a go?

Takeaway Points

- Taking a dialogic approach to reflective mentoring conversations is a great opportunity for subject-specific mentoring practice.

- When observing it is important to keep history specific areas for development at the forefront of your mind and to provide history-specific feedback in post-lesson conversations and written feedback.

- Observation of other history teachers is really good professional development for both mentors and mentees.

Victoria Crooks is Associate Professor and Subject Lead for the History PGCE at the University of Nottingham. Laura London is Subject Lead for the History PGCE at the University of East Anglia. Victoria and Laura worked with Professor Terry Haydn to co-author Mentoring History Teachers in the Secondary School, published in 2024.