In the summer term of last year I asked my Year 7 pupils a question: Why did religion matter to medieval people?

One of the first answers both my Year 7 groups came up with was ‘it gave them a shared sense of identity’.

This surprised me at the time. This wasn’t the answer I was first expecting.

But I am confident that the reason for their response was the sequencing of the substantive concept of identity in our curriculum.

Previously I wrote a blog for the HA which focussed on how my department planned to incorporate a small number of organising substantive concepts into our curriculum.

For Practical Histories, I will focus on how we have practically implemented repeated exposure to a substantive concept across several units of the curriculum to help provide a schema that enables pupils to explore the past with richness.

Why identity?

As with many of the ‘organising’ substantive concepts that we use in our curriculum, identity itself is a new social concept developed by sociologists in the 1950s.

As James D Fearo argues: “Identity is a new concept and not something that people have eternally needed or sought as such. If they were trying to establish, defend, or protect their identities, they thought about what they were doing in different terms.”

However, it is worth noting that while this concept in the form we are using it was not used by contemporaries in the periods we are studying with all of our pupils, this term can still be transhistorically applicable and historically useful (as long as we acknowledge it wasn’t a term used at the time).

Historians can ask what it meant to be English in the Norman period even if it wasn’t explicitly wasn’t talked about at the time, as Marc Morris does in his book, The Norman Conquest, just as we can ask what it means to be English today.

As Wineburg argues historical thinking entails building a clear situation model or mental representation of the history being analysed.

Disciplinary concepts such as causation are a way historians superimpose concepts from the present onto the past to create useful situation models to help us interpret events and actions in the past.

Substantive concepts like identity may be similarly useful in enabling pupils to think about the past in cultural and social terms.

Identity in our Key Stage 3 curriculum

While we return to the concept of identity throughout many of the enquiries in our curriculum, those highlighted below represent schemes of work where we return to them in greater detail.

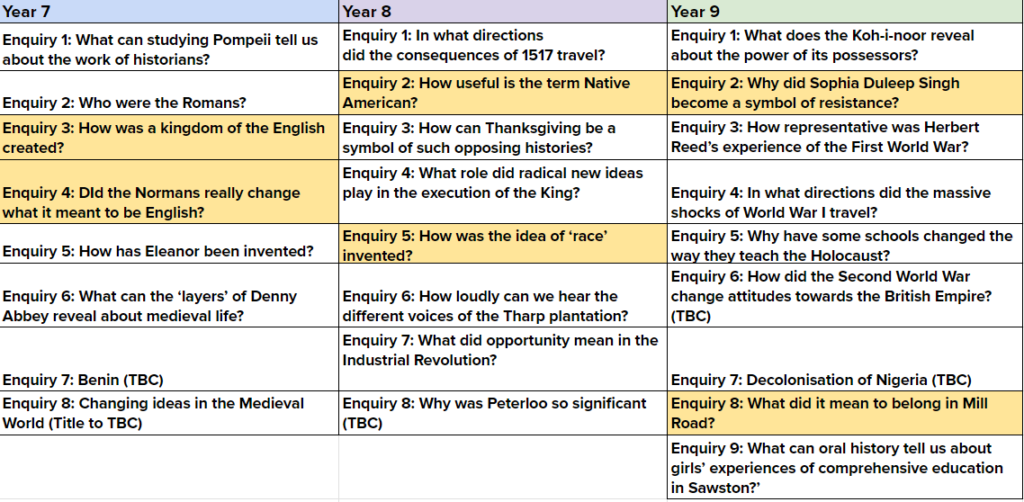

Sawston Village College’s Key Stage 3 History curriculum below, has key enquiries linked to identity highlighted in yellow.

As a result of basing two enquiries on Marc Morris’ scholarship, Year 7 pupils explore both national identity through an enquiry ‘How was a Kingdom of the English created?’ and changing group identity through the enquiry ‘Did the Normans really change what it meant to be English?’, where pupils explore how the identity of the peasantry, for example, changed during Norman England.

In Year 8 pupils explore issues around imposed identities through the enquiry How useful is the term Native American?.

During this enquiry pupils judge how far a label given by white colonisers to Native Americans is an appropriate one to use.

Later in the year, they explore why labels were also imposed on different ethnic groups through the enquiry How was the idea of race invented?. By Year 9 pupils are looking at complex identities on a more personal level.

Through close cultural analysis of a range of oral histories pupils explore What did it mean to belong on Mill Road 1962-88?

Furthermore, in an enquiry on Sophia Duleep Singh, pupils judge how far Duleep Singh’s family identity or her active participation played a greater role in her becoming a symbol of resistance.

Step 1: Pupils’ first encounters with identity

The first time our pupils come across identity is in the first scheme of their History curriculum where they look at ‘What can studying Pompeii tell us about the work of historians?’

We use etymology to break down the origins of the word (just taken from a google search “etymology: identity”) and establish a basic sense of what identity is using a simple definition of the word.

Pupils then apply this to an account of the eruption at Pompeii by Pliny the Younger and think about what we can learn about Roman identity from this story.

In enquiry two of the year, when pupils are reasoning with a similarity and difference enquiry called Who were the Romans?, they are then asked to try and recall what they think identity might mean.

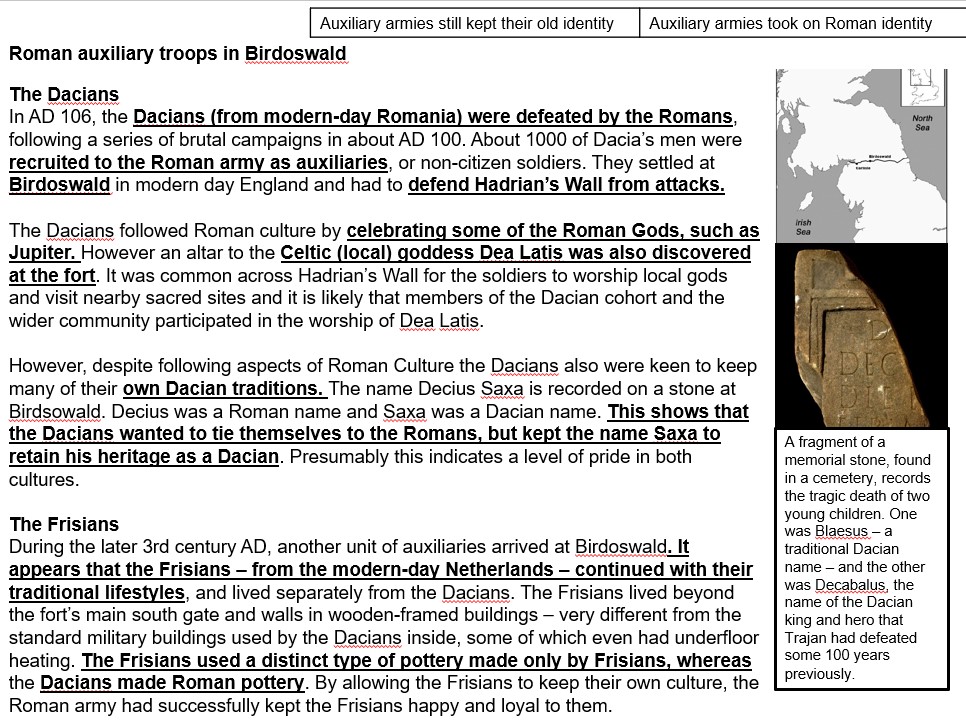

The etymology is given to pupils again as a starting point. This time, however, pupils are asked to start to think about the difference between Roman and Dacian identity through a case study of Roman soldiers at Birdoswald Fort on Hadrian’s Wall.

Pupils explore a range of evidence about the Dacians practices and traditions – including the names they chose and religious practices they used.

This enables pupils to see identity as being fluid – what traditional Dacian practices were maintained, but also what they had taken on from other Roman soldiers.

This comparison of identity enables pupils to see how identity can be constructed and defined by people themselves.

Step 2: Exploring National Identity

In their third enquiry of the year – How was a kingdom of the English created? – pupils explore the work of Marc Morris Anglo-Saxons.

This enquiry question was created by Elizabeth Carr and discussed at her History Association presentation in 2021.

However, we have developed our version of the enquiry by breaking down the concept of national identity for pupils to explore.

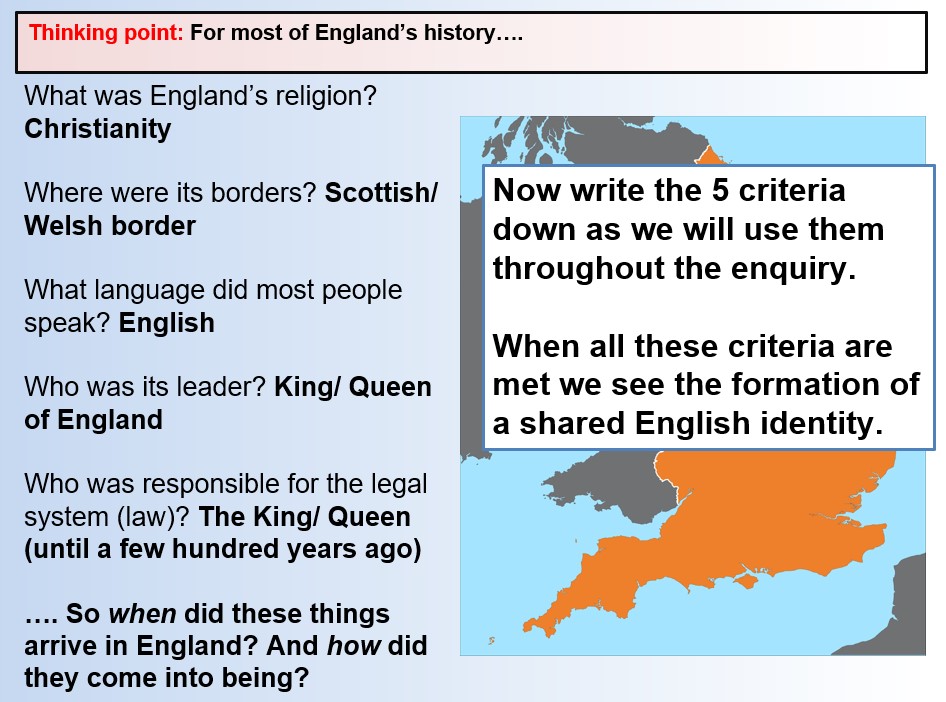

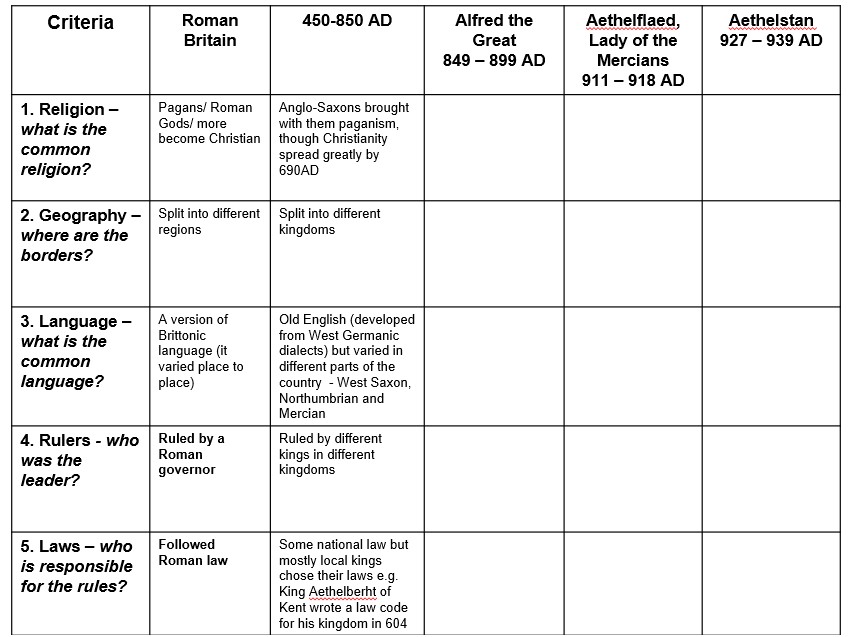

Pupils were given a set of simplified criteria (see picture of the slide below) to support them in establishing a framework to decide when an ‘English’ identity was created.

We explore the reigns of Alfred, the time of Aethelflaed and the reign of Aethelstan and ask pupils to write an extended piece in which they argue which ruler they think was most important in creating English identity.

While we acknowledge the simplified criteria is hugely oversimplifying the nature of identity construction, these categories were formed out of methods used by Anglo-Saxon Kings like Alfred and Aethelstan to create and establish their Kingdoms: through imposing new language on coins, establishing their image as ruler through the use of crowns, to their attempts to spread Christianity and expand their borders.

Stage 3: Developing an understanding of changing identity

Once pupils have explored national identity in depth through the Anglo-Saxon enquiry, our next enquiry explores how the identity of the English changed under the Normans.

The inspiration for this enquiry came from a quote in Marc Morris’ book The Norman Conquest which argued that “The Conquest matters, in short, because it altered what it meant to be English”.

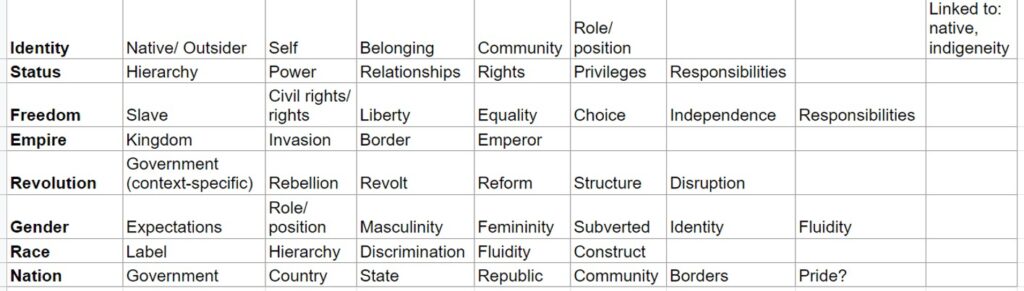

As explored on my original blog post for the HA, one of the first things we did as a department in our project to develop substantive concepts throughout our curriculum was to develop a shared understanding of the substantive concepts we were teaching.

We broke down concepts by thinking of words and vocabulary that would help pupils understand the concept and enable them to attach it to existing schema.

This is similar to the process undertaken by Dhwani Patel where she broke down the concept of authority into both power and legitimacy.

By exploring the nature of the vocabulary precisely, and understanding the nuanced differences between authority and power, pupils were able to explore the medieval past through richer mental models.

We spent time as a department doing this for all our concepts, and then used these broken down concepts to support question creation.

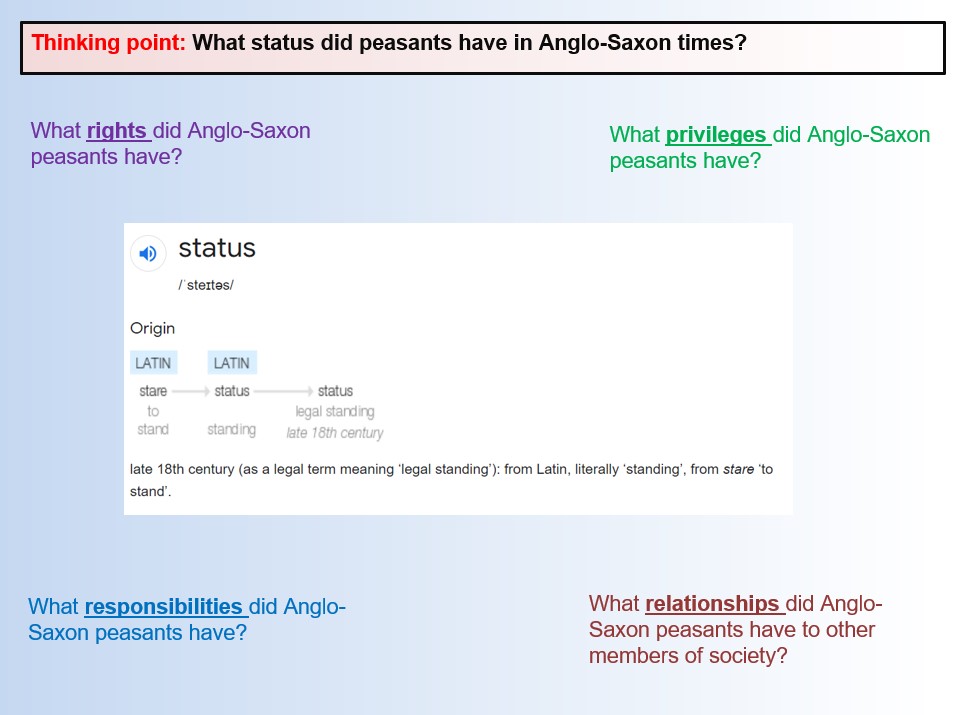

To support pupils thinking about Norman identity, I created the following questions to get them to think analytically about change through the lens of identity and to help pupils understand how people defined themselves under Norman rule: Did roles/ positions within society change? Did people’s sense of belonging change? Did people’s experience of their community change?

These three questions were used repeatedly throughout the enquiry and some, such as status, were broken down even further during a lesson on the peasantry:

While it might seem on the surface these extra questions added complication, by prompting pupils to think explicitly about the nature of identity and status more deeply and its connection to other words, it was more likely to activate their existing mental models and provide them with a framework to understand the concept.

To show these ideas manifested in pupils’ answers I have included here example outcome paragraphs from the enquiry on the Normans (PDF). NB spelling, grammar and factual errors have been left in.

Conclusions

It is clear in all these outcomes, that pupils’ repeated exposure to the concept of identity had enabled them to construct, at least to some success, a mental model of changing English identity.

The unpacking of identity enabled pupils to make interesting inferences linked to the concept of change.

However, I also think these repeated encounters with identity, have served pupils beyond this enquiry.

Pupils were able to approach later enquiries with a pre-existing rich mental framework. When I asked my pupils in our next enquiry on Eleanor of Aquitaine the question ‘why did religion matter to medieval people?’ they therefore already had rich understandings of the role of religion in identity creation.

While I hadn’t ever asked pupils that question before, they were able to apply their knowledge of identity from both the Anglo-Saxon and Normans enquiry to a new question.

Complicating pupils’ understanding of identity, and creating rich mental maps of its meaning through connected language, has provided our students with a useful framework for approaching the past and this is why we will endeavour to build up similar richness around other concepts.

This year we are working as a department on using the concept ‘radical’ as a means to provide fruitful mental models for Year 8.

Sarah Jackson-Buckley is Head of History at Sawston Village College, Cambridgeshire and the Subject Community Leader (History) for Anglian Learning. She also has responsibility for leading Literacy in her school.