Dr Alison Morgan explains why she would love to go back to The Romantic Era.

When I shared my idea of writing about the Romantic Era as the period I would most like to visit with my daughter, she regaled me with the lack of rights for women, transatlantic trade in enslaved people, appalling living and working conditions for the labouring classes and an oppressive state.

Indeed, the historian Robert Reid describes England at this time rather alarmingly as coming closest to “the early years of the Third Reich than at any other time in its history”.

And yet, I countered, despite all that, it was the Age of Revolution, a time in which some of the finest minds wrote some of the greatest works, new philosophical and political ideologies were forged in the heat of revolution, scientific breakthroughs changed our view of the world and orthodoxy was challenged on almost every level.

The Age of Rights

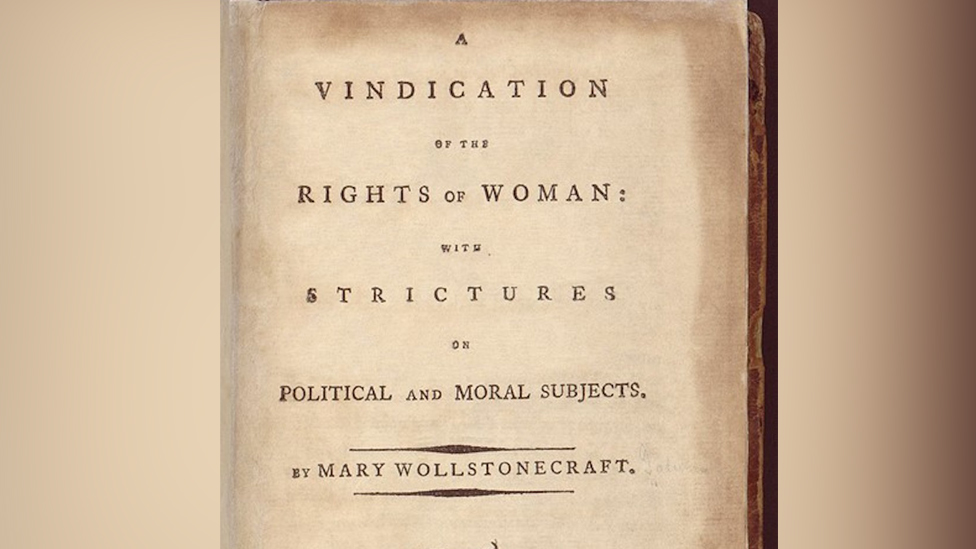

It was also the age of rights: from Thomas Paine’s ground-breaking The Rights of Man to Mary Wollstonecraft’s counter text, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman; campaigns for the rights of men, women, children and animals, together with the abolition of slavery.

All of these interventions galvanised huge swathes of the British population resulting in protest, rebellion and the wholesale challenging of societal norms.

Spanning the era from the French Revolution in 1789 to the Great Reform Act of 1832, this compressed period witnessed some of the most significant events in British history.

The aftermath of which are still felt today. A walk around any of our cities reveals the legacy of industrialisation, from the cotton mills of Lancashire to the pot banks of Stoke.

Much of our current political ideology has been shaped by the brilliant minds of Paine, William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, their proto-Marxism and feminism opening minds to alternative ways of living.

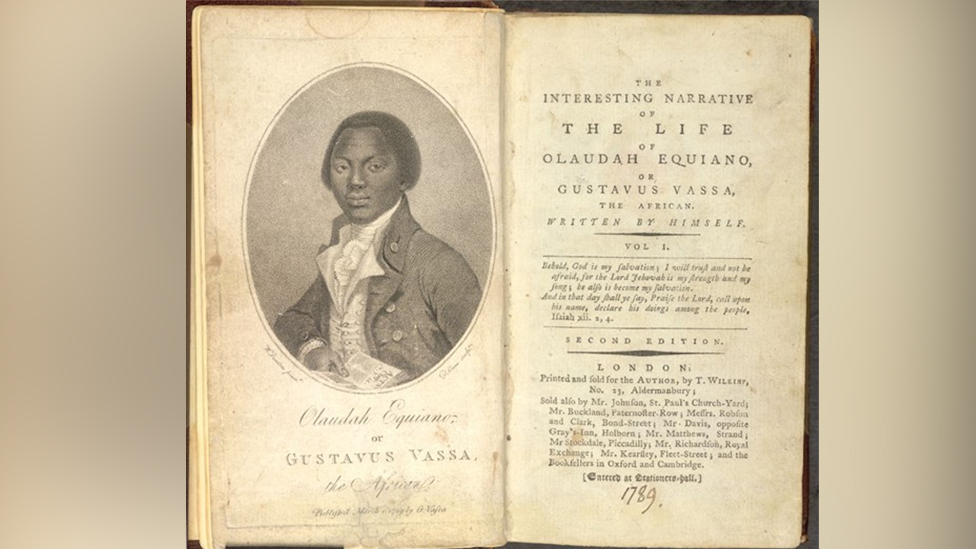

Furthermore, the voices of the poets William Blake, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and abolitionist, Oladauh Equiano, among so many others, still echo loudly.

Indeed their understanding of the human experience as relevant today as it was 200 years ago.

Poetry

My fascination with this era began when, as an English undergraduate, I discovered that the Romantic poets did more than write about daffodils and nightingales and I was particularly inspired by the raw political power of the poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley:

Rise like lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number

Shakes our chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you –

Ye are many – they are few.

Reading this famous refrain from Shelley’s masterpiece, The Masque of Anarchy, for the first time in Thatcher’s Britain during the miners’ strike, I understood the power of poetry to convey a political message.

The poem was described by the literary scholar Kelvin Everest as “perhaps the greatest English poem of radical political thinking” and written frantically and furiously in 10 days following the news of the Peterloo Massacre in 1819.

Shelley managed to harness the rage expressed by people against the authorities butchering men, women and children in Manchester who were simply campaigning for the right to vote.

Like many of his contemporaries, Shelley was fully aware of his dialectical role in being both a creator and creation of the age in which he lived.

Labouring Classes

While Shelley’s poems on the state of the nation in the 1810s are remarkable sociopolitical documents, part of the reason I am championing the Romantic Period is that the voices of the labouring classes can be heard loud and proud in the radical newspapers, pamphlets and ballads which blossomed at the time.

They captured the towering injustice of their lives with wit, intelligence and irreverence.

If you want to really know what life was like in radical circles of the time, take some time to read Thomas Spence’s deliciously-named journal, Pigs’ Meat, its title a satirical play on Edmund Burke’s famous description of the people as “the swinish multitude”.

Interweaving original songs with extracts from 17th Century polemics, Spence’s revolutionary exhortations for the redistribution of land are redolent of the soundscape of this era when voices of the ordinary people mingled with the intelligentsia in a cacophony of a call to arms.

Bravery

So, even though my daughter is right to state that so many people living in the Romantic era had few or no rights, the campaigns for a better country burgeoned in this most repressive of times.

I hugely admire the bravery of the men and women who risked so much to get their voices heard, espousing a British patriotism based on ideals of inclusivity and liberty in opposition to discriminatory and venal regimes who were only interested in serving themselves.

So, don your cap of liberty, grab banner emblazoned with the motto “liberty or death” and march with me on the streets of London in 1816, Manchester in 1819 or Bristol in 1831 where we will join thousands protesting for freedom against a tyrannical regime. Raise your voices and sing:

“Rouse, rouse, loyal Britons, your fame to maintain,

Nor tamely submit to wear slavery’s chain,

Like Britons stand firm in humanity’s cause,

Asserting with spirit your rights and your laws.

Dr Alison Morgan is an Associate Professor at the University of Warwick where she is the deputy head of the postgraduate secondary teacher-education programme.

- Tags: Enlightenment, History, Literature, Romantics, Where in history