Associate Professor Tom Haward encourages us to use visual historical sources critically. They can offer unique ways of seeing the past in their own right, rather than being relegated to illustrating text.

The following list is in the form of some pragmatic tips for working with visual sources in the history classroom today.

I hope they inspire you to think further about the use of visual images, and maybe even put some of these ideas into practice.

Visual sources need dedicated ‘thinking time’ in the classroom

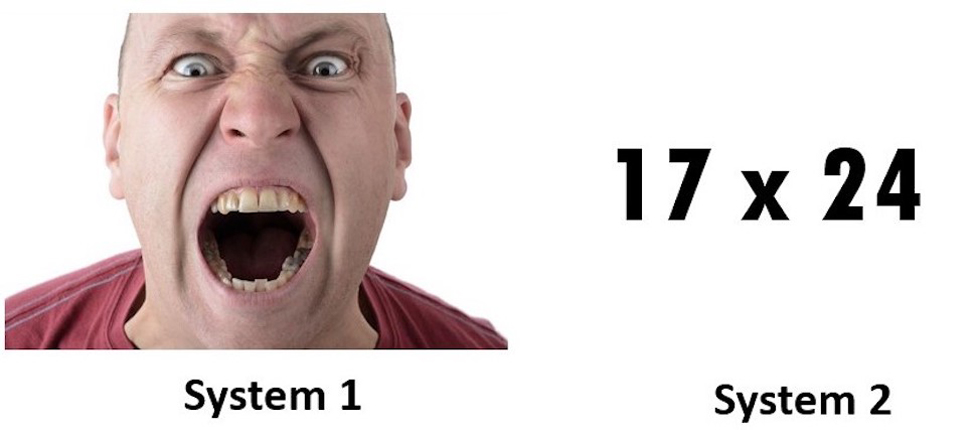

Daniel Kahneman in Thinking Fast and Slow (2011) describes two “systems” of thinking.

System One operates ‘automatically and quickly, with little or no effort’. When we see an image of an angry man, the anger is conveyed instantly. System Two, however, involves “effortful mental activities”. When working out 17 x 24, most of us will require some time to process this.

Many visual historical images contain both System One and Two types of thinking. As teachers, we need to encourage students to go beyond System One and give time to consider some of the more complex ways of understanding them.

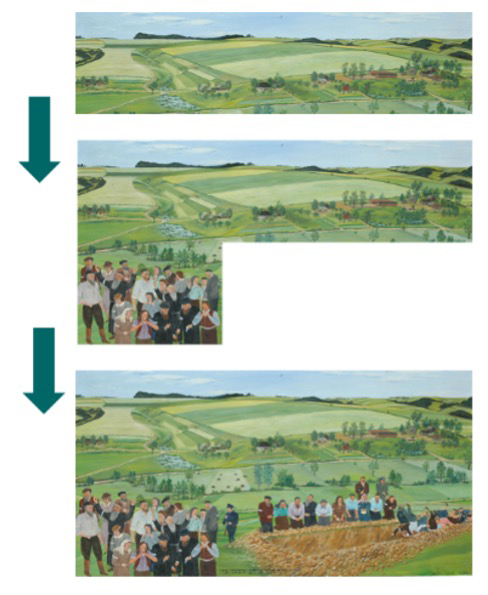

You can slow down students looking at visual historical images by… revealing them piece by piece, rather than as a whole.

Using a layered approach to viewing an image can invite students to look more closely and invite them to create hypotheses about what it’s depicting, and why.

To do this, just show one part of an image first – in this case the rural scene in the top half of the image – and then reveal more and power parts. Each time, ask students what they can see and what narrative this image might be trying to convey.

This can be much more engaging and develop thinking more effectively than showing the whole image at once.

This example show how a seemingly calm, pastoral scene draws student attention to the contrast between the top half of the picture and the bottom half, which can be shocking and provocative when it is revealed.

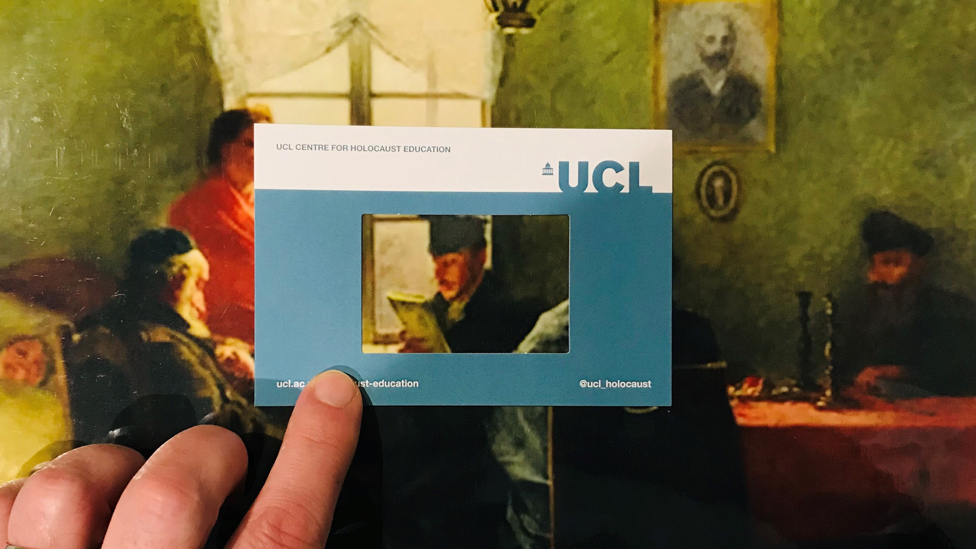

You can slow down students’ looking at visual historical images by … using a viewfinder

I’ve adapted this great idea from the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Physically holding a viewfinder in their hands helps students to take their time and select features of an image that may go to explain the whole – in this case it could be the candlesticks, or the Judenstern lamp hanging from the ceiling.

I’ve used a viewfinder – a piece of card with a whole cut in the middle – in an iteration of our UCL Centre’s lesson, Who were the 6 Million?, which looks at Jewish pre-war life through the painting Sabbath Rest by Samuel Hirszenberg (1890).

This can be found in the Ben Uri Gallery Museum and Collection (see Resource Links below).

Visual sources need effective questioning

Effective questioning avoids bombarding students with comprehension-style questions, but instead allows space to explore and interrogate historical images.

Starting with some observational questions is helpful in establishing what it is students are looking at. Then move on to more inferential and analytical questions, which with careful teacher guidance, can also come from students themselves.

Examples of these that I have found useful might include;

Observational Questions;

- What can you see?

- How might you describe it?

Inferential Questions:

- What does this tell you? How can you tell?

- What can you be certain of?

- Why might this image have been created?

- Who is the intended audience?

- How, and why, has the artist used techniques such as colour and light and dark?

- What might this image say about the time it was created?

- Does this image matter to us today? If so, why

Images often say more about the times they were made, than what they are attempting to show.

Jane Card calls this “double vision,” which she describes as “one period’s visualisation of another” (History Pictures, 2008). She uses the painting, The execution of Lady Jane Grey by Paul Delaroche (1833), to show how the image can tell us more about the Victorian era and the Romantic movement that produced it than it can about the Tudors.

Many Victorians enjoyed dramatic and sentimental pictures – but, in reality, the scene would have occurred outdoors on Tower Green and she wouldn’t have been wearing a white dress.

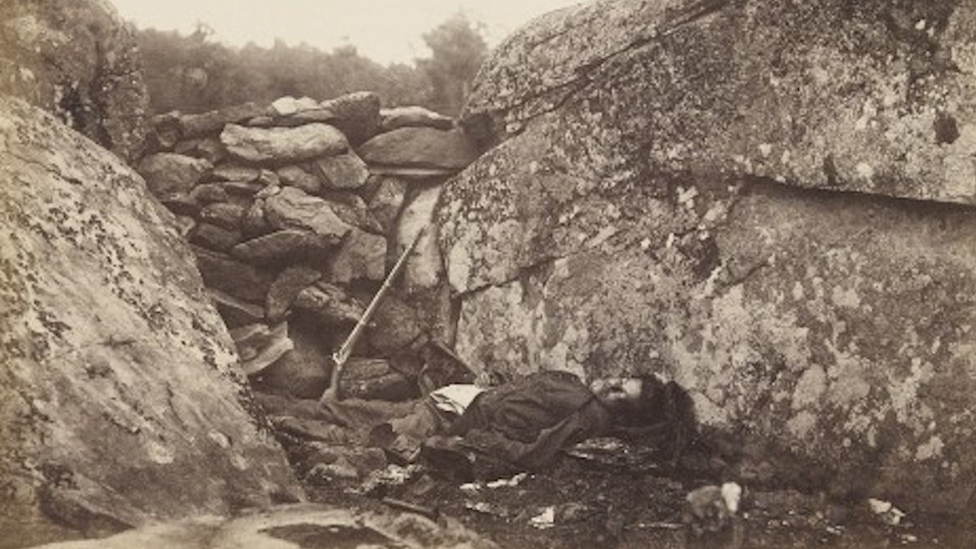

Students need to interrogate the truth claims images may make

Many images, including photographs, can make truth claims that need to be unpicked.

Photographs may implicitly claim to be truthful: a moment of reality is captured for the viewer to better understand what really happened.

This photograph was taken by Alexander Gardner at the end of the Battle of Gettysburg.

He called it Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg, July 1863. The American Civil War came at a time when photography of war was first gaining prominence.

Their impact shocked many Americans. This image is a construction, however – the body has been moved, and the rifle was added for dramatic effect.

Students need a level of critical literacy that goes beyond the face value that images main claim to show, and goes deeper to consider questions of authenticity.

Consider the ethical implications of using images

Using images in the classroom comes with ethical responsibilities too. The use of atrocity images is hotly debated, and something this author avoids. Before using any image, though, a few tips include;

- Avoiding distorting, distending or cropping images

- Attributing images where possible

- Using original captions

- Particularly with atrocity images, remembering there is a duty of care for the students in a classroom. Some questions you may consider are; What might you hope to achieve by doing showing atrocity images? What specific contextual ethical grounds might there be for not showing images? Does it matter who had taken the image, or why?

Try juxtaposing images

Juxtaposing images, or considering the sequence they are shown in, can help ask questions of the past that may not otherwise be apparent.

A particular way that can be effective is showing a similar scene or motif in different time periods – this can ask questions of students about the nature of historical change and continuity.

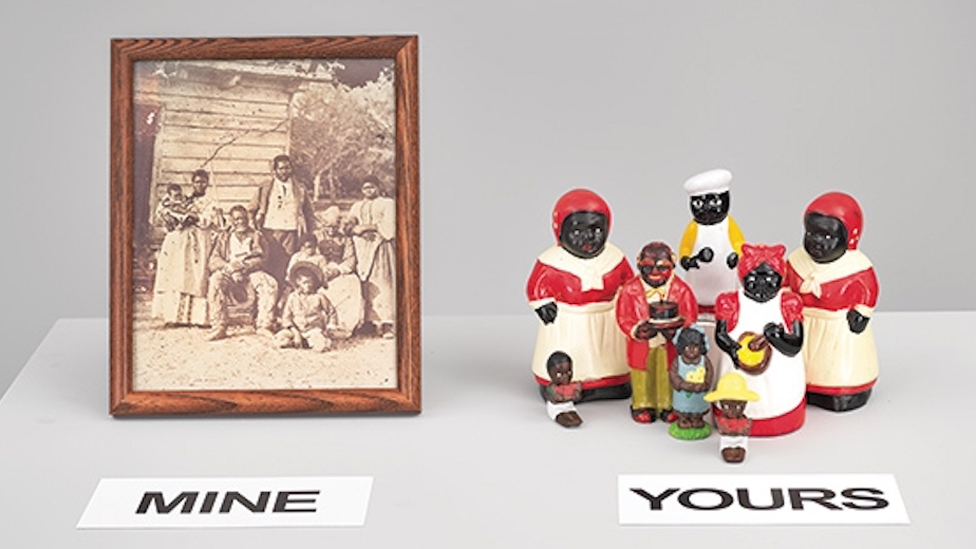

I particularly like the work of American artist Fred Wilson and the way the juxtaposition of images in Mine/Yours (1995) of black African-Americans in the era of slavery asks questions of identity and the kinds of cultural constructions that are created over time, and to what ends.

In summary

Research and teaching experience suggests that when working with visual historical sources in the classroom.

- they have a visual impact in their own right that can engage students

- the pedagogical approaches chosen matter.

- they need to be seen as complex historical sources, with agency, in their own right and not just as illustrative adjuncts to text

- they have the potential to subvert and interrogate dominant narratives

- students experience a variety of ways of engaging with them that are dependent on complex contextual factors

- images can speak more about the times they were produced than the time of the event itself

- they have the capacity to be rich, powerful interpretive tools

- students need time to work with visual images

- they can benefit from being seen as distinct spatial puzzles and representations that need to be understood within the specific context of their medium.

- students of all abilities can engage with them in sophisticated ways.

Tom Haward is Associate Professor at the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education. He has over 20 years’ teaching experience, has carried out research into visual learning at the University of Brighton and holds a University of Sussex doctorate in how visual sources are experienced in the teaching of History.