Lou Cash provides a compelling argument as to why it’s important to make the most of the historic environment and offers loads of practical ideas to use on a visit to one of the country’s most famous buildings.

Can you pinpoint the moment when you fell in love with history?

For me, it was on a summer’s day in 1989, standing on Guildford High Street holding a black clipboard and a pencil with a sparkly rubber on top.

On a GCSE local history visit, I spent a couple of hours making pencil sketches of the buildings, debating whether the Tudor Rose Restaurant could really be Tudor, examining old maps of the town and comparing them to what I was looking at, listening to stories of the discovery of an Anglo-Saxon mass grave across the valley and pondering on the etymology of the name Guildford.

Was it the golden flowers or the golden sand that gave this shallow river crossing its name?

We then spent a further hour or so investigating the parish church of St Mary’s in Quarry Street and trying to get to grips with how and why the building changed over time.

That site visit was where my love of History and much of my curiosity about the world stemmed from. History was exciting – there were puzzles to solve right in front of me. I think it was part of an SHP GCSE course. The local study is still important for SHPers now.

To this day I struggle to walk past a pub sign or a road sign without briefly wondering about the history behind it.

Having worked at Westminster Abbey as a learning officer for over ten years, it’s no surprise that I advocate for giving young people a chance to experience historic environments.

As we welcome hundreds of school visits from KS1 up to KS5, who usually select a History or a RE focus, we get to share our excitement for the space and its history both onsite and virtually.

I know that school trips can be a lot of work to organise, so I thought I’d share some of my top tips to make sure that students get the most out of their experience.

The examples I’ve used are based on Westminster Abbey, but everything can be applied to a historic site local to you. Image of students on guided tour of Abbey.

The mystery element

Another exciting spot is the strange staircase built into the side of a wall. It doesn’t seem to come from anywhere and it doesn’t lead anywhere either.

Students have a lot of fun working out what it might be for.

Unexpected architectural features like these are so useful for helping students understand that buildings change over time as their function alters.

Maps and plans of the site encourage students to work out where they are standing and to look for possible solutions to the architectural puzzles.

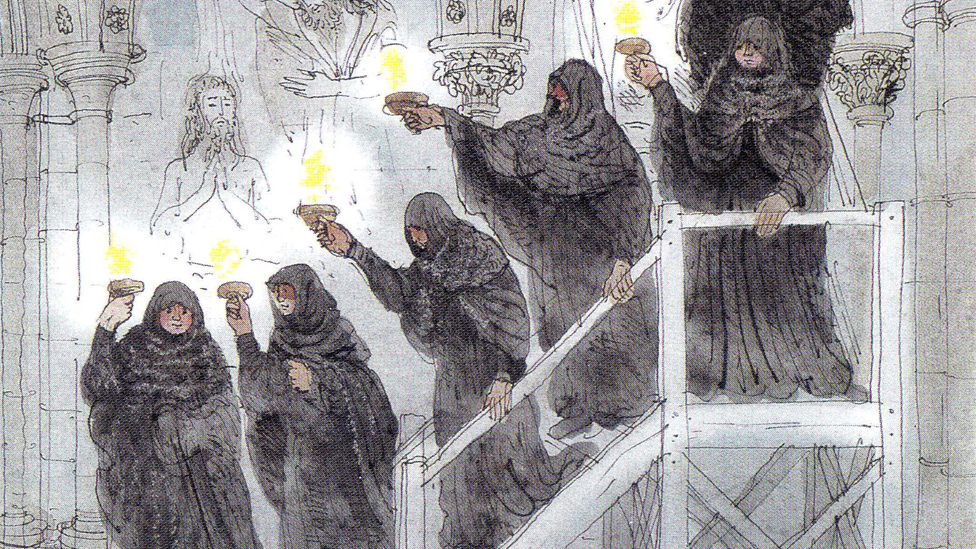

Benedictine monks founded Westminster Abbey in 960AD. For almost 600 years the rhythms of monastic life continued here unchanged.

The monks began the cycle of daily prayer with Matins at midnight and ended with Compline around 8.00pm. The mysterious staircase gave direct access from the monks’ dormitory into the church, bypassing the cloisters, and so was used for the nighttime prayers.

After the monks left in 1540, the building was modified, the dormitory was re-purposed, and some windows were blocked up. Even little puzzles can provide a sense of mystery and excitement to a site visit.

If you don’t know the answer to something that is puzzling, so much the better. ‘Let’s see if we can work it out together…. what can we surmise?’

Change the perspective

Looking at things from a different perspective is a useful thing to do in life generally and is vital for students of History.

Look for opportunities to observe the site from a distance as well as close-up, from a low vantage point and a high one.

This ties in with the idea historians being parachutists which the Annales School used so adeptly in their approach to our wonderful discipline.

The bird’s eye view of a site is tricky to manage. Since opening the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Galleries at the Abbey, we can offer schools that option.

The Galleries house the Abbey’s Museum collection and are situated 52 feet above the Abbey floor giving an incredible view once described by John Betjeman as “the best view in Europe’”

It is thought that this space was originally designed to house private chapels, but it lay empty for 700 years, used only by spectators at coronations.

From this vantage point, the entire coronation ceremony could be viewed – from the grand, public entrance at the West Doors to the moment of coronation itself, directly below the viewpoint, on the stunning Cosmati pavement.

As well as looking down at the Abbey, the Galleries bring us much closer to the vaults.

It is now possible to see the level of craftsmanship that went into every detail. This 13th Cebtury corbel would have been invisible from the congregation on the ground floor which begs the question, why did medieval stonemasons put so much effort into work that would never be seen?

Objects in focus

Narrowing the view can be just as interesting as widening it.

Providing students with a simple cardboard viewfinder can be a useful and inexpensive item to take on a site visit.

Get students to look through it and find a detail of the site they like.

Sometimes a historic building can seem overwhelming and asking students to zoom in on one detail can really help their confidence. They can become an ‘expert’ on something by examining it closely, sketching it and thinking about how/why it was made.

One of the most beautiful parts of the Abbey is the fan vaulted 16th Century Lady Chapel.

It is almost too splendid to contemplate in one sitting. The Tudor historian John Leland described it as “the wonder of the world”.

There is so much here that looking closely at just a few objects can be very helpful.

The gold ceiling motifs are a good place to start. The double rose, the portcullis, the fleur-de-lys could be considered in terms of what they represent and what they tell us about Henry VII- selected as they were by him to adorn his chapel.

The monument to Henry VII and Elizabeth of York with its highly ornate grille, dominates the east end of the chapel.

A closer look at the monument reveals repeated images of a greyhound and a dragon.

These objects in focus are a useful starting point when thinking about Henry’s ancestry and his motivation in spending over £14 million on the building of this chapel.

A visit to the Abbey’s Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Galleries will bring you face to face with Henry VII (or at least his well-preserved effigy).

Perhaps the question could be put to him?

Tell a story

Ofsted’s research review of History teaching (July 2021) reminds us that “storytelling is a powerful vehicle for learning”.

If walls could talk, the Chapter House walls at Westminster Abbey could tell a tale or two.

Built in the 13th Century, they were originally painted with Biblical images – fantastical beasts and tortured souls inspired by the book of Revelation.

They looked on, as the monks gathered here every morning to listen to readings from the Rule of St Benedict and listened in, as the monastery business of the day was discussed.

The walls were privy to meetings of the King’s Great Council and the emerging English Parliament.

Then on 16 January 1540, they watched as the 24 remaining monks led by Abbot William Boston processed into the room and signed their names on the Deed of Surrender, handing over control of the Abbey to Henry VIII’s ministers.

In so doing, 600 years of monastic life ended here in a single moment.

There’s nothing like telling the story of Dissolution standing in the Chapter House on a wintry January day. You place your feet where the monks placed theirs and you look around you at the painted walls as they must have done.

Among the biblical images that decorate the room are portraits of people from a bygone age, staring out at us from the silent walls as they stared out at the monks in January 1540.

This is where the power of storytelling brings a static room to life. What better way to explain that students are standing in a place where history happened?

For more stories about the Abbey listen to our Chronicles from the Corbel. There are ten to choose from and each links to an object from the Galleries.

Engage the senses

Multi-sensory experiences are so important, and the temptation is to leave them behind once students get to KS4 and above.

The Learning Outside the Classroom Manifesto argues that “What we see, hear, taste, touch, smell and do gives us six main ‘pathways to learning’.”

A site visit at any age can be transformed with some simple and inexpensive sensory props.

Sketching, listening to a piece of music linked to a site and encouraging students where possible to touch the building materials at the site.

How does the material feel? Does it feel warm or cool? Why might this material have been used? All are all manageable activities on a site visit.

The sense of smell is closely linked to memory and whilst the Abbey has its own unique and ancient smell it is also home to the 900-year-old College Garden, thought to be the oldest garden in England.

In monastic times, it was used to grow food and medicinal herbs for the occupants of the Abbey.

Today there are beautiful lawns, fruit trees, well-stocked herb and rose gardens with plenty of opportunities to stimulate the olfactory senses.

It is a calm, beautiful place to visit on a trip to the Abbey and provides a good space for groups to reflect on their visit.

In some ways, there has never been a better time to organise history outside the classroom.

There are less people about and, if you were to visit a site or a town like I did way back in 1989 you will be outside for the day.

You could, if you are near enough, visit Westminster Abbey in person.

Without the crowds, there is quiet and space to enjoy the building at a more leisurely pace. With over 1,000 years of stories to tell, each person who walks through the Great West Doors adds to those stories and will walk away with their own experience, whether they have a faith or not.

We want young people to feel excited, to feel inquisitive, even to feel challenged by what they see while in a historic environment.

From those who learn a thing or two and enjoy their day out of school to those who might have that ‘Guildford High Street’ moment, we welcome them all.

Book your school’s onsite or virtual visit on the Abbey’s website.

Lou Cash is a Learning Officer at Westminster Abbey and freelance writer of education materials.