In an era of fake news and conspiracy theories, how can history teachers ensure the importance of truth and integrity are fully understood by pupils?

In spite of the difficulties of fitting things in, given the limits on curriculum time for history in schools, this short article makes a plea for the importance of trying to squeeze in some attention to the issue of truth in history, and in society today.

As with attempts to develop pupil understanding of time and chronology, this might best be done not in the form of whole, discrete lessons, but occasional and intermittent mentions, asides, brief opening-it-up discussions where topics relate to uncertainties and difficulties of ascertaining an authoritative picture of an event or person, or one of the many contested issues in history.

Some homeworks might direct pupil attention to issues related to truth, quotations about the importance of truth can be put on classroom walls.

The aim would be to gradually build up pupil understanding of the complexities involved in truth, history and present day life.

The Problem with Truth in Schools History

Truth is an important but problematic facet of school history.

Part of the problem is moving students beyond a ‘naïve realism’ approach to the idea of truth in history – the belief that there is one definitive correct and 100% accurate version of everything that happened in the past.

Tony Sewell’s recent suggestion that an official textbook would be commissioned and deployed in all schools to teach children “the truth” about modern Britain (he said that the idea had been successfully deployed in Russia – quoted in Savage and Iqbal, 2021), suggests that it is not just adolescents who struggle to understand the relationship between truth and history.

There is, however, another dimension to the issue of truth in schools history, which is sometimes neglected in current curriculum arrangements.

Although the issue of interpretations of the past receives appropriate attention in curriculum specifications, textbooks and writing about the teaching of history, less attention has focused on the importance of developing pupils’ understanding of the concept of truthfulness or veracity, in the sense of the ethical importance of making an honest attempt to provide the most accurate explanation possible from the evidence available.

This is in spite of the fact that respect for evidence is of central importance to the discipline of history, and lack of respect for truth and evidence is currently a major problem in many countries, including the UK.

If schools history is to make a full contribution to the good of society, as well as the good of the individuals studying it, we need to cultivate pupils’ understanding of the importance of respect for truth and evidence as a moral and ethical issue, rather than a purely intellectual one.

As I have argued elsewhere, many of the bad things that are currently happening in the world are done by people who are very clever, did well in history at school and who often have high-level qualifications in history.

They probably have a perfectly sound understanding of interpretations, evidence, change, cause, significance etc, and many of them have perfectly adequate subject knowledge.

But they do not have the slightest concern for truth. (Just think of some of the high profile current and recent world leaders and give them a mark out of ten for honesty, truthfulness, integrity).

In the same way that a differing degree of regard for truth (in the sense of not making an honest attempt to provide the most accurate explanation possible from the evidence available) is one of the differences between good and bad historians.

It is also one of the differences between good and bad scientists, journalists and (often hugely influential) media presenters.

Pupils need to understand that truth, honesty and integrity (part of the aims, values and purposes of the National Curriculum up to 2007, but since excised) are important at a personal level.

They also need to understand that they are important civic virtues, as pointed out by Confucius, Aristotle, Sen, and a slew of recent books on the dangers to society posed by the recent ‘assault on truth’.

This lack of concern for truth is becoming an increasing problem for liberal democracies because the past two decades have seen a number of significant changes in the fields of knowledge production and dissemination, technology, culture and politics.

These developments have implications for the aims, purposes and practice of school history.

One of the changes which impacts on young people’s ideas about history is the proportion of information about the past that they receive from digital sources which are unmediated by the professional historian, the history textbook writer or the history teacher in schools.

As Shemilt and others have argued, given these recent changes in knowledge production and dissemination, unfiltered access to the past may be doing more harm than good in the modern world.

Perhaps, like smoking, history should come with a health warning.

As Simon Schama argue: “What we have which has never happened before is the robust existence of a flourishing fantasy world”

A world of systematically disseminated untruths and the technology to make those fantasies, conspiracies and untruths instantly, massively and widely available through the internet.

How history teachers can combat bad history?

The weaponisation of history is not a new phenomenon.

There have always been people who have attempted to use knowingly distorted stories about the past for unethical purposes.

What has changed in recent years is both the amplification effects of modern social media, and the financial benefits which can be derived from the promotion of sensationalist conspiracy theories which go viral on the internet.

As it is not possible to shield young people from the sometimes dubious histories advocated by (some) politicians or promoted by some newspapers and social media feeds.

History education needs to address the problem of the bad history that is out there, rather than ignore its existence.

In the light of these changed circumstances, part of the aim of school history needs to be to educate students about the differences between good and bad history.

A good way of doing this is to show them examples of bad history, to explain way it’s bad, how unscrupulous people try to use history to manipulate the public, and what techniques they use, so that pupils understand what game in being played by these versions of the past.

Given the sophistication with which information can be manipulated and distorted in contemporary society, and the harmful effects that bad history is currently causing in society worldwide, it is more important than ever that history teachers devote some time to address these facets of public history as well as academic historiography.

This means teaching pupils to be able to discern between serious and rigorous or respectable history, harmless history which is primarily for entertainment (Blackadder, Braveheart, Horrible Histories etc), and history which attempts to distort the past for sinister and nefarious purposes.

They need to be able to challenge distorted and emotive manipulations of the past when these are presented in support of present day political objectives.

One mistake is to think that it is just about improving pupils’ cognitive skills in handling information intelligently.

The work of Ben Walsh Sam Wineburg, Mike Caulfield and others in stressing the need for pupils to be digitally literate in using sources from the internet is useful and important.

As well as providing pupils with the intellectual tools to discern between authoritative claims about the past, and meretricious, misleading and flaky historical narratives and explanations, it is also necessary to imbue students with a sense of the ethical importance of making an honest attempt to provide the most accurate explanation possible from the evidence available from the past.

This is because there is evidence (from the many recent books explaining the post-truth turn in modern societies), to suggest that some people do not appear to object strongly to being lied to, and prefer to believe comforting narratives and explanations which support their preconceptions and play on their prejudices.

Young people need to be taught explicitly that respect for evidence is of central importance to the discipline of history, and that lack of respect for truth and evidence is a major problem in the world today.

Seven practical teaching ideas

There are several things that history teachers might do to develop pupils’ information literacy and understanding of the importance of truth, in history and in life.

Developing pupils’ digital literacy

When dealing with provenance issues and sourcework, as well as mentioning the work of Caulfield, Walsh, Wineburg and others in history education who have drawn attention to the importance of digital literacy as part of a historical education relevant to the 21st Century, try to develop pupils understanding of words and concepts such as astroturfing, amplification, bots, gaslighting, dead catting, sockpuppetry, trolling, doxing, the manufacture of consent, playing the race card.

It can also be helpful to point out to pupils that there are some reputable fact checking sites available on the internet to help to ascertain the reliability of stories circulating on social media, such as Full Fact, Snopes and others (plus a warning that there are some sites which masquerade as fact checking sites that are not what they seem).

Things might have changed, but I have been surprised by how few people seem to understand the phenomenon of astroturfing – see Bienkov 2012 for a helpful pupil-friendly explanation.

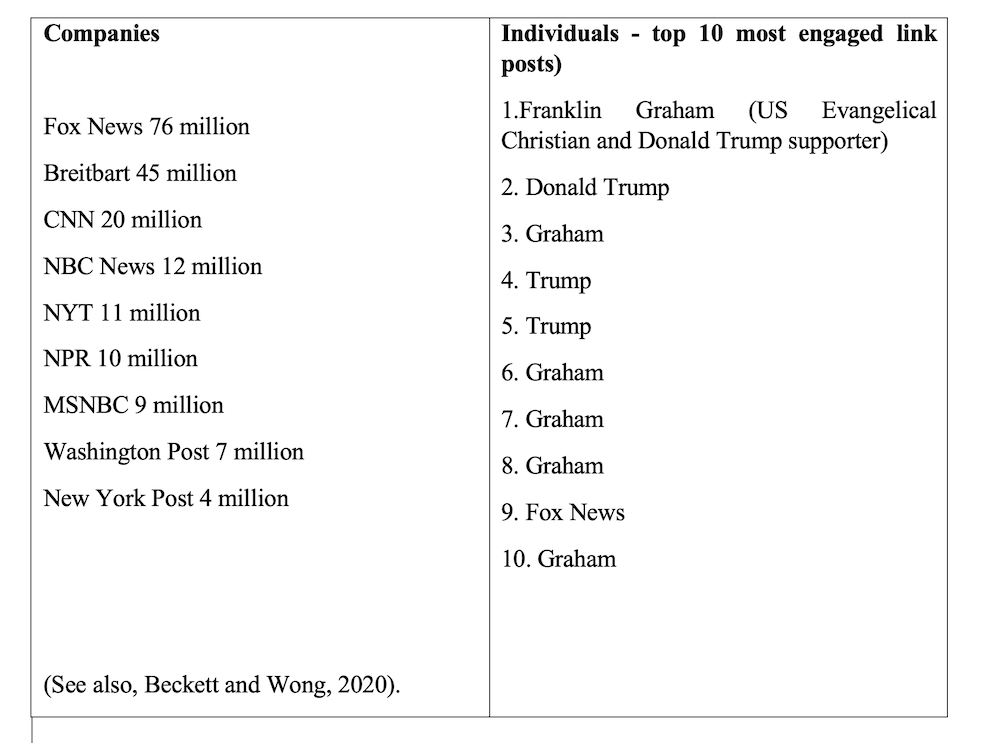

A good example of the amplification effects of social media, which sheds some light on the enduring popularity of Donald Trump can be found in the following tweet that I stumbled on, which shows the scale of exposure to Trump-supporting organisations:

Companies

Rutger Bregman’s Davos speech provides a good example of diversion – where those in power attempt to divert public attention from issues which might adversely affect their interests by using their influence to get the media to focus on other agendas.

Showing and deconstructing examples of ‘bad’ history

Given the quantity of awful history now in the public sphere, it is not difficult to find examples of ways in which the historical record has been subverted and distorted for immoral and unethical purposes.

These examples need to be presented to pupils and deconstructed, in order to give learners an understanding of the ways in which history can be manipulated in order to serve present day purposes – whether through appeal to emotion over reason (particularly with reference to stoking anger and fear of outsider groups), the use of selective citation and sophistry, the appeal to nostalgia and sentimentality, the oversimplification of cause and consequence and the setting up of heroes and villains.

In this way, pupils can learn to understand what tricks are being played with the past, what sort of game is being played.

Learn our History’s The Reagan Revolution is an entertaining example of crude but well financed bad history.

MP Daniel Kawczynski’s insistence that the UK received no money from Marshall Aid post World War 2, and that all the money went to ‘Europe’, and his refusal to back down on this claim is a good example of ‘doubling down’ on a lie about the past.

Donald Trump’s claim that George Washington’s army ‘took over the airports’ in the American War of Independence is a different sort of bad history.

Bill Cash’s explanation for the outbreak of World War 1 (‘Max Hastings, Michael Gove and Boris Johnson all say: ‘Let’s get it right, Germany started the first world war’) manages to helpfully combine selective citation with grotesque oversimplification in a single sentence.

It can be helpful to include examples which are clever and seductively done (see, for example, Rumsfeld on Bin Laden’s caves).

Handled skillfully, this can contribute to the development of students’ critical faculties, ability to think for themselves, and resistance to being manipulated.

Educating pupils about different types of bad history

There is also a need to educate pupils about the different forms that unreliable and untrustworthy history can take, and the differing motives for the formulation and promotion of such history, from the monetised clickbait of social media provocateurs, to the need for newspapers and news sites to sell copy and attract viewers and advertising, to the less sinister (but still flawed) bromides of popular history designed for easy reading and serialisation in the newspapers (see Morris’s, 2013 article entitled, The Limits of our Knowledge, in The Historian, for an eloquent description of such histories relating to the events of 1066).

It also includes the peddling of sanitised, nostalgic, feelgood and Disney-fied myths about the national past.

This should ideally extend to developing pupils’ understanding of the limitations of (many) TV programmes and school textbooks, with their unproblematic and essentialist ‘this is what happened’ narratives.

There is also the “let’s say something controversial” tendency of some celebrity historians.

Getting pupils to understand the pressures on veracity

It is also helpful if pupils understand that there are often pressures that militate against telling the truth, in terms of constructing a story about the past.

Politicians will be politicians, and sometimes try to use history to validate their policies. Journalists, scientists, researchers sometimes have a vested or financial interest in shading the truth.

Power structures within an organisation may well militate against ‘telling the whole truth’ (one might make the point that things have not gone well for many of the most famous whistleblowers in history – many of them told the truth but at some personal cost).

Historians are not always completely objective, and have their ‘positions’, backgrounds and need to tell a story which will evince the interest of reviewers and the media.

Keith Jenkins notes that historians are often keen to suggest resonances between the past and present because if they don’t, their story won’t be read.

There may even be a moral case for not telling the truth in some circumstances – consider the dilemma of administrators in the Chernobyl disaster, where complete honesty may have sparked mass panic.

Getting pupils to understand that lies have consequences

If we want to get pupils to care about truth, we need to get them to understand that lies often have serious harmful consequences, from the ‘Stab in the Back’ legend in post World War I Germany, to the Chernobyl Catastrophe, the persecution of Sandy Hook victims after the Info Wars conspiracy theory propagated by Alex Jones, the gun massacres committed by believers of ‘The Great Replacement’ in the US, the deaths caused by lies about the safety of the Boeing 737, or the Volkswagen emissions scandal.

There is also, perhaps the biggest and most consequential lie in history, Exxon’s denial of climate change. A lie that may well have severe consequences for all of us.

Using quotes about the importance of truth

Just a few examples; the advantage here is that it doesn’t take up any precious curriculum time. These would make excellent classroom display statements:

“The teaching of history has to take place in a spirit which takes seriously the need to pursue truth on the basis of evidence.” – Sir Keith Joseph, former Secretary of State for Education.

“The objective of the superior man is truth.” – Confucius

“Why do you care so much about laying up the greatest amount of money and honour and reputation, and so little about wisdom and truth?” – Socrates

“Truth is certainly a branch of morality and a very important one to society.” – Thomas Jefferson

“Respect for truth comes close to being the basis of all morality.” Frank Herbert

“The ideal of keeping records fairly and honestly a first priority for historians.” – Wong -Chinese historian.

“You cannot be a liar and a historian” – Susannah Lipscomb.

Asking the question, ‘What does the historical record say about this?’, and using this as the foundation for an enquiry approach to a historical issue

This can be done alongside brief explanation of the ways in which claims about claims to historical knowledge are validated (as with science and other disciplines) – by peer review of the judgements of the community of practice of professional experts in the field (as opposed to whatever is posted on the unmediated morass of social media).

A good example here, is reviews of Christopher Clark’s ‘The Sleepwalkers’, where a wide range of reputable professional historians testify to the accuracy and dependability of Clark’s findings.

It means of course, being at least reasonably knowledgeable about the ways in which the issue in question has been approached within the community of practice which represents the discipline, and being careful to accurately reflect the balance and range of historiographical views on the issue in question, without feeling obliged to represent the views of those outside the ‘respectable’ community of professional practice (for example, Holocaust denial websites).

The Teaching History feature What are Historians Arguing About? is an excellent resource in this respect, and really useful for helping to get pupils beyond the ‘naïve realism’ misconception about history and truth.

One of my sad hobbies is to collect quotations about the aims and purposes of school history.

One of my favourites is by Sir Keith Joseph, partly because it references the part that respect for truth should play in the teaching of history in schools.

The website also has a collection of resources on managing pupil behaviour which might be of interest to anyone mentoring student teachers.

Terry Haydn is Emeritus Professor for Education at the University of East Anglia.