Ian Dawson provides you with ideas to make your history lessons more practical. By using physical activities and positioning pupils to different places in the classroom you can really help them understand some tricky concepts.

One of the most important aspects of teaching is identifying why students may struggle to understand a topic and then planning teaching to help them overcome those learning problems.

This applies with every age-group from primary school to undergraduates and beyond.

Just to make this more challenging for new teachers, there’s a variety of different reasons why students may struggle – they may have unspoken misconceptions about a topic or period; they may be unable to visualise a conceptual idea you’re discussing; they may think they’re the only one who’s struggling and not voice their uncertainty.

There will also be occasions when your most crystal-clear and erudite verbal explanation doesn’t produce the magic solution.

It’s therefore worth exploring other solutions such as simple ‘physical’ activities which involve movement in the classroom – using your students as props for your explanation and other excitements.

This article briefly describes four such activities and why they may be worth using.

Despite this article being written during the time of an unprecedented global pandemic, I hope you will be able to use this kind of activity when you return to full class teaching.

In the meantime, I have included brief ‘Covid alternatives’ (even though they’re repetitive) and thank the PGCE trainees at the University of Sussex for prompting this.

Helping students get to know ‘Who’s Who’ – Creating Human Diagrams

Students lose confidence when uncertain about ‘Who’s Who?’ in any new topic and that uncertainty niggles away, undermining their efforts to learn.

Therefore getting a grip on names and how those people fit into a new topic is vital, whether at A level, GCSE or across a longer period at KS3.

Elizabethan England

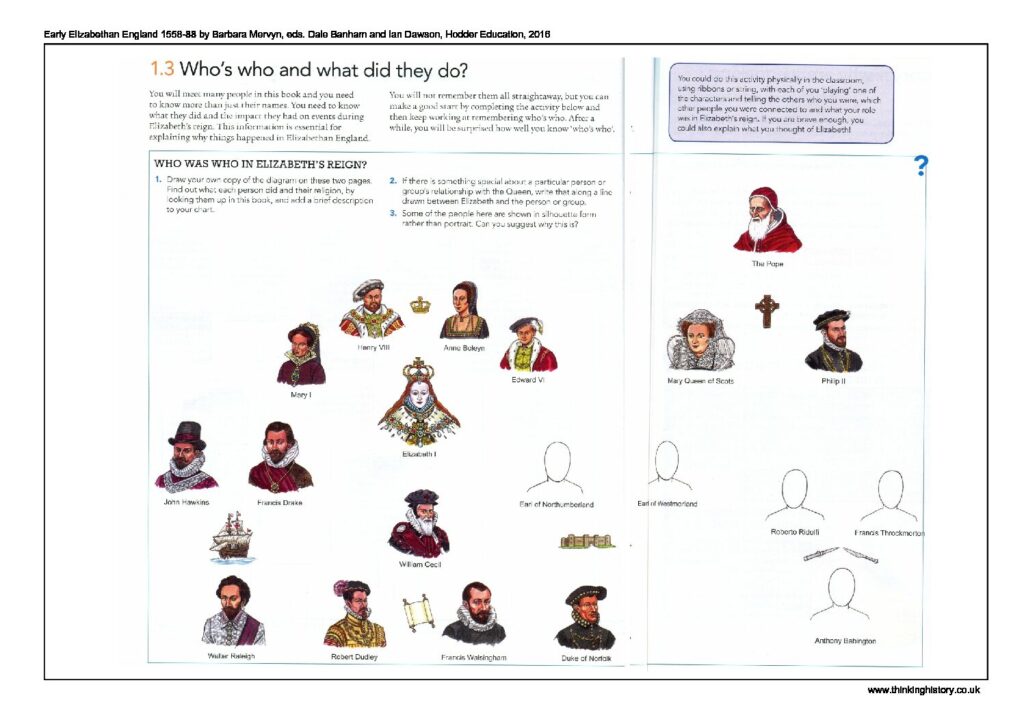

This activity helps students get to know Who’s Who faster, using Elizabethan England as an example.

The idea is to create a human diagram with students (wearing tabards with names on) acting as one of the people from the period, placed in the ‘diagram’ in relation to Queen Elizabeth and grouped by role (eg seafarers or Catholic plotters).

However, the complete diagram is not where you start. Build it up as follows:

Preparation – allocate each student an individual and set them the task of finding out about their individual and his or her relationship to Elizabeth. Maybe use friends to represent connected individuals eg seafarers or cast students with the same names as historic individuals.

In your lesson, build up the diagram by asking students one-by-one to place themselves in relation to Elizabeth.

Draw out the reasons for the placement from each student. Students who don’t have roles can draw and annotate their own diagram.

To consolidate memory, ask students individually or in pairs to recreate the diagram on paper, adding annotations to explain groupings, attitudes to Elizabeth and links.

The human diagram could be photographed to create freeze-frame images, then students add speech or thought bubbles to explain their relationship with Elizabeth or use the photographs as a display and ask students to recall and explain the links.

Here are some helpful notes from Carmel Bones on using this activity – I encourage use of the accents eg “I am Roberto Ridolfi” in best Italian. This can make it memorable and ‘memory sticky’ – and hushed tones for the Catholics adds a bit of light and shade!

The shape of the reign can be understood too from this visual representation – assigning an epithet to each decade can elicit some interesting thoughts eg ‘the danger zone’ for the 1580s.

A bag of props (again not Covid-safe at the moment) can also enhance the proceedings – rosary beads, coins, toy ships, prayer books etc.

Returning to the activity later will help consolidate memory. This especially important when we are working at time where Ofsted define learning as being able to “know more and remember more”.

Possibilities include:

a) Recreate the human diagram and ask individuals to tell the story of an event from their point of view, explaining their actions OR to give their views of the actions of another individual.

b) For A level – choose a year and ask students to create their own diagram ie who would be in the diagram in 1520 but not in 1545 and would they be in the same positions related to Henry VIII. Or place students in a pattern and ask them which decade or year this pattern represents.

As a Covid alternative – give students a partly-begun diagram and list of names to add. Ask them to complete the diagram and discuss in class. Next week ask them to build the diagram from scratch.

Helping students see patterns across time – One Student equals Two Million People

How can we help students quickly see long-term patterns of change and continuity – such as population across time?

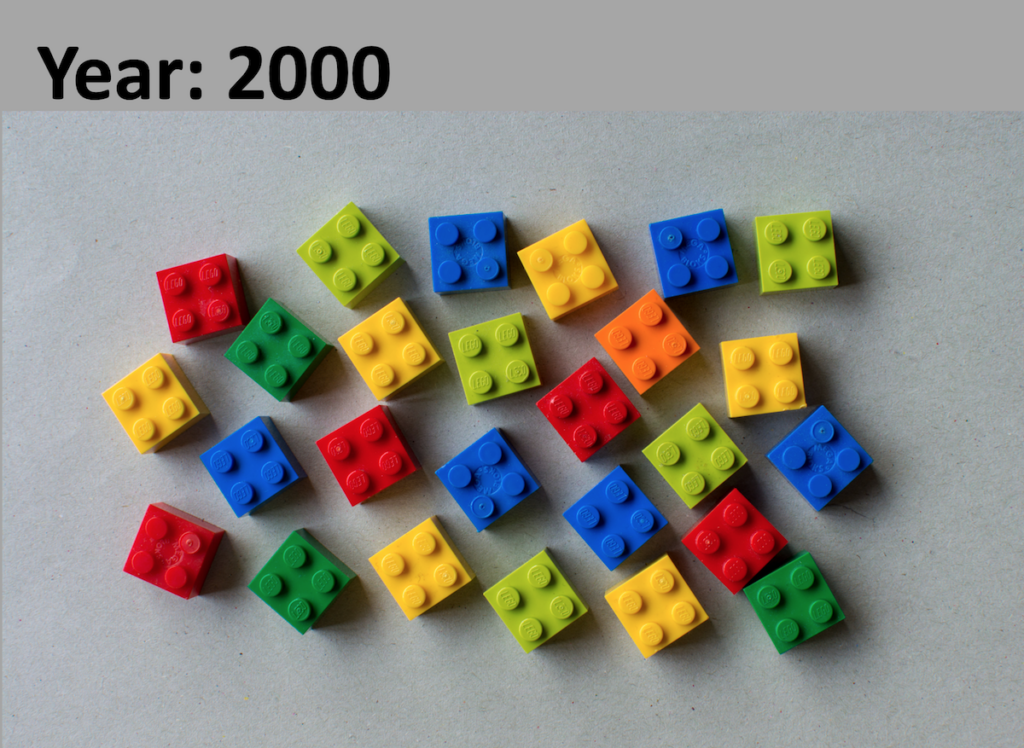

One solution is to use students to represent the total population with one student representing roughly two million people. So how does this strategy work?

a) Ask students to predict the pattern of population change from whatever date you wish to begin up until today by offering options on slides e.g. the pattern as a series of ups and downs or as gradual steady increase.

b) Spread the class round the sides of the room, leaving a large space which represents Britain.

Tell students they represent the population of Britain c.2000 – and so each of them represents two million people. Richard is two million, Aaron is two million etc.

Then ask students to suggest how many people there would have been in Britain at the time of the Norman Conquest or whenever you begin.

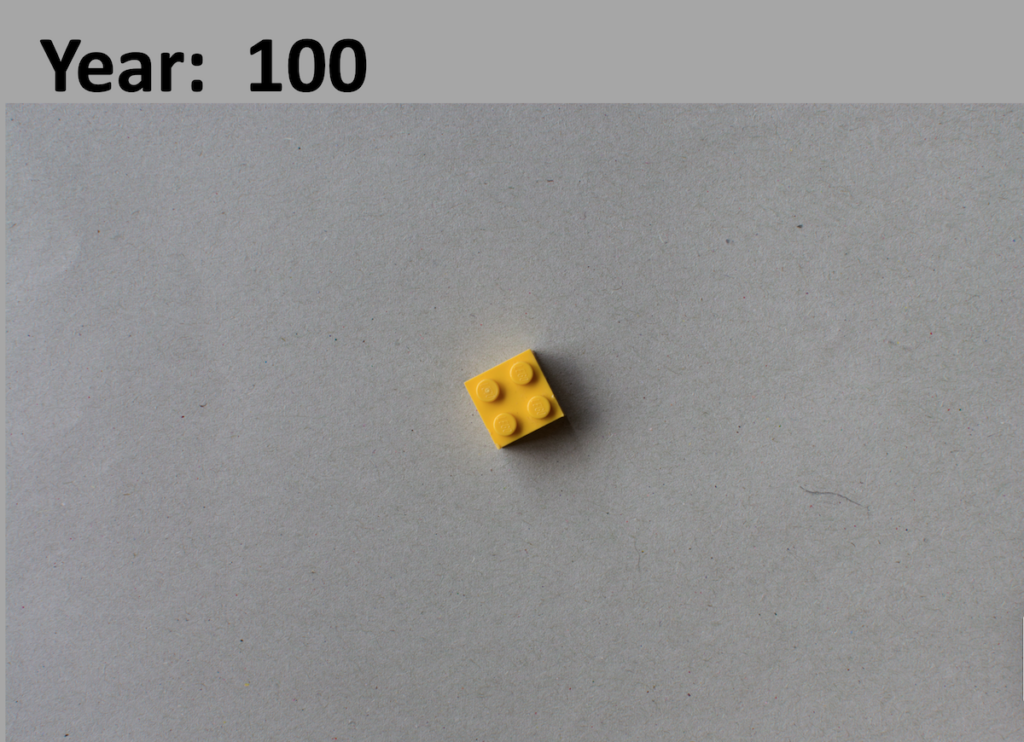

c) Build up the overview across time by moving through century by century, adding or taking away students as the population increases or falls. (One million equals a student kneeling down).

Do this quickly (you’ll find the numbers at the link below), mentioning periods and some well-known events to help them keep track of where they are in time.

However, don’t explain the changes in population so that students need to think for themselves.

d) Ask them to explain what surprised them or what fitted their expectations, then to describe the pattern from memory, maybe giving them vocabulary prompts such as change, continuity, stagnation, turning points. Focus on the pattern.

e) Ask students to suggest:

i) reasons for continuities and changes in the pattern e.g. plagues, nutrition, medicine etc

ii) the consequences of changes in population eg demands on governments, need for food and housing, quality of life in towns, epidemic diseases, crime rates etc.

This activity is worth repeating more than once during KS3 or GCSE Themes so that students relate it to conditions within individual periods and develop their understanding of the consequences of population change.

Covid alternative – use the slides in the Download Resources box below which show Lego pieces instead of students.

Helping students put England/Britain in context – Using your room as a map

Using your room as a map and students as countries or political leaders is a very effective way of helping them understand the bones of a narrative, the structure of alliances and the motives of those involved in ‘great events’.

In the examples below, the strategy can also be used to correct misconceptions about how England/Britain fits into the wider European pattern of political power.

If such misconceptions aren’t challenged they undermine students’ chances of understanding the issues they’re studying.

Example 1. Henry VIII and Europe

This is the beginning of a lengthy activity exploring Henry VIII’s foreign policy at A level. It challenges students’ likely assumption that the apparently dominating figure of Henry VIII was the mainspring of European events who could easily have an impact on events and helps them appreciate the reality that England was a country of limited power in the 16th century.

Arrange your students geographically to create the map of Europe. Start by choosing two or three students as ‘England’ and nominate one of them as Henry VIII. Then choose someone to be ‘the Scot’ – not a major role but an important reminder that England had to be aware of the threat of Scottish invasion when contemplating European involvement.

Next allocate students in larger numbers as France, Spain and the Empire – say eight for France, six for Spain etc. Identify the rulers with named tabards. Finally, select a Pope and maybe individual students to be small Italian states.

The physical map emphasises that English power, population and wealth are far less than those of other nations.

However we can take this further by demonstrating that the focus of much international interest was on Italy, not in north-western Europe.

To do this explain the wish of France and others to gain territory in northern Italy and make everyone turn to look towards the Pope and the Italian states – make a great show of everyone (apart from the Scot) turning their backs on England and Henry.

This shows England was on the fringe of European politics and that Henry VIII would have to do something special to achieve his aim of European glory and to match rival kings.

It also has the great advantage of being memorable ‘do you remember when Matt was Henry VIII and the other countries all turned their backs on him?’

Example 2. William AND Normandy

1066 – William becomes King of England and … does Normandy matter anymore? Students at all levels may assume it doesn’t.

This activity helps students appreciate that William ruled a cross-Channel empire and that England was not his sole focus. William crossing backwards and forwards across the Channel on numerous occasions and spent 80% of his time in Normandy after 1072. Creating a human map helps get these ideas across.

Use students (wearing tabards) as places – set them out as England and Normandy and as William’s potential enemies in Anjou, Maine and Brittany, Denmark and Scotland.

Then explore possible dangers for William – who might take try to take advantage of his absence from Normandy? How might he try to prevent attacks on Normandy? Who would he leave in charge? Would he want to stay in England for long? Why would rebellions in England pose a threat to his control of Normandy too?

These are all questions that students will gain more understanding of if they are discussing them while looking at or taking part in the physical map. Similarly you can explore the dangers to his control of England from Scots or Danes if he’s in Normandy.

Covid alternatives for both examples above – demonstrate on your table at the front using soft toys, lego pieces etc or build up on slides. It’s not the same but it’s better than not tackling these misconceptions it at all.

Helping students ask good questions – why was the King being whipped?

Enquiry questions have played an increasing part in structuring teaching since the 1980s and much effort is expended on framing the ‘best’ questions.

But this may be at the expense of helping students develop the ability to ask good history questions themselves.

This is one example of using a physical activity to prompt students to come up with their own enquiry question – good for motivation and good for encouraging them to see asking questions as an important historical skill.

For me, the best question to ask about the murder of Becket is “Why was Henry II whipped in 1174?” as this requires a broader range of understandings of society than does the ‘murder mystery’ approach.

The king had huge power but didn’t have complete freedom of action.

If he had, he wouldn’t have needed to use his penance to buy the Church’s help in 1174 (nearly four years after Becket’s murder) against rebels among his own family and his barons.

This activity has two parts – the question-asking set up and then a card-sort enabling students to build an answer.

This description deals with the first part only. I’ve provided questions to ask – it’s up to you how you juggle the answers as it’ll vary from class to class.

Place skeleton (apply to Science dept) or a willing volunteer on the floor. Ask students – where do you think we might be?

Turn on background music (Gregorian chant?). What does this suggest about where we are?

Place one student kneeling in front of the ‘body’. Ask – what do you think s/he’s doing?

Give the kneeling student a crown to wear. Ask – who do you think s/he is? What’s happening in this scene?

Now explain that this is Henry II kneeling at the tomb of Archbishop Becket.

Line up six or eight students standing alongside the king. Ask – who might they be? what do you think is going to happen next?

List the answers.

Explain what happened next – some are bishops who whipped Henry five times each, the others are monks who whipped the king three times each.

Ask – what questions do you want to ask? It’s all been aiming at the prompting the question “Why did the king agree to be whipped?” so try to steer in that direction!

Covid alternative – use skeleton or large teddy bear as Becket and add more toys to taste.

Some conclusions

Two practical problems:

What do you do if you only have five or six students? Two possibilities – use empty chairs to simulate the numbers or, if available, use cuddly toys.

Some of you might think your A Level students would be insulted by the use of stuffed rabbits as French councillors.

But that’s only if you don’t explain why you’re using these methods and how it will help students learn more effectively.

A touch of fun and laughter does not undermine the intellectual rigour of the exercise! I’ve used such activities many times at final-year degree level and explaining why I’ve used the approach does win suspicious students over.

Two more concluding points:

You can’t just assume students have learned what you hope they will learn. Always create time for a specific debriefing by asking that most challenging and important question– ‘what have you learned today?’

These activities are not only about the history but can also help students learn independently more effectively.

Taking the ‘Who’s Who?’ activity as an example – next time they start a topic with lots of new names remind them of their first use of this activity – what was the problem they faced?

How could they use that activity this time? Discussing how students can solve their own learning problems is fundamental to good teaching.

It’s essential to make learning visible in order for it to be self-sustainable by students who have learned how to study independently.

Ian has retired from involvement in history teaching several times but continues to write resources for teaching on medieval history on thinkinghistory.co.uk