Lindsay Bruce discusses the importance of raising literacy levels in your classroom. She explains the barriers and then, using different examples offers you a whole host of ideas to improve your practice.

For those of you who ‘eye-rolled’ when you saw the title of this article – I get it.

You may work in a setting with a Whole-School Literacy focus that means you have multiple laminated pieces of paper stuck to the wall. You are reminded to focus on literacy but are given no clear guidance on how you make that subject-specific.

Perhaps you have just started or just finished your training. You may have had a generic lecture on literacy. But now you have started teaching you’re not sure what you include that in a pre-planned curriculum that appears to leave no room for manoeuvre.

The barriers

Literacy is important but it is often not done well. As Geoff Barton stated recently in OUP’s Word Gap report; it must be planned on a whole school level.

I totally agree, but as teachers, the whole school vision is realised by what we do in the classroom. And, the whole school literacy policies vary from school to school.

Also, there is a strong argument that as History teachers we ‘do’ literacy all the time. This is because of the nature of the subject. Our first order concepts, key terms and a focus on explaining, analyzing and making judgments means we incorporate literacy into all of our lessons.

For some students this is fine. They will absorb the subject-specific vocabulary required, and they will build an understanding.

It has been argued, that this is largely because they were exposed to a wide range of vocabulary by the age of 4. According to a 2016 study by UCL Institute of Education:

“Early spoken language skills are the most significant predictor of literacy skills at age 11. One in four (23%) children who struggle with language at age five do not reach the expected standard in English at the end of primary school, compared with just 1 in 25 (4%) children who had good language skills at age five”

Being Explicit

It’s that reason that means other children need more explicit literacy instruction – they are working at a deficit.

We, therefore, have a responsibility to be explicit with our content. This should be mapped out consciously throughout the key stages. Basically, key terms, subject vocabulary, and command words should build the sequence of learning. As Christine Counsell stated in Debates in History Teaching in 2017, ‘We make our encounters with new material take on meaning by assimilating them to prototypes formed from our past knowledge’ It is so important that first-order concepts (such as empire, parliament, war, monarchy, revolution, etc.) are taught and revisited in different guises to show that words/concepts can have multiple meanings. This should stop students feeling that they are ‘starting again’ when they reach GCSE.

So how can we, as classroom teachers, ‘do’ literacy?

Some possible solutions – word banks

When I wrote the Word Gap resources for Teachit and OUP I argued that we should use word banks. And, that they could be a great resource to use if students play a part when they are being collated.

This will help you to address any misconceptions students have about key terms and provides an opportunity for students to hear the words spoken aloud. This in turn can help to embed new vocabulary.

Research by Schmitt suggests that students need to hear a word 10 times before they become confident in understanding and applying it to different contexts.

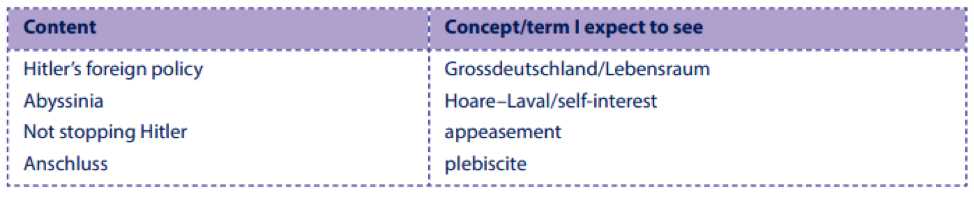

Word banks can be used to introduce new vocabulary in a knowledge organiser, or as a way of matching content to key terms you would expect to see in their writing.

They can also be powerful tools for getting students to review their work before the dreaded ‘I’m finished’ klaxon sounds. Much needed training for when they sit in the dreaded exam hall in Year 11.

Both of these activities have proved useful as a retrieval tool; the students rank their confidence using a simple 1-5 rating – with particular terms and then weeks, months, years later we go back and track our confidence with those same key terms, using them as a spark for the content taught.

For example:

| Word | Date Used | Confidence Rating |

| Imperialism | 9/9/20 | 2 |

| Imperialism | 21/9/20 | 2 |

| Imperialism | 10/11/20 | 4 |

Furthermore, if the concept or term in the new context has a new meaning I can judge how well my students have grasped that. If they don’t get it, we can’t progress.

What you talking about?

One of the key ideas that left me convinced that literacy was something that needed to be focused on was when I learned about the Matthew Effect.

By heavily differentiating work, rather than scaffolding, it is those rich explanations that students miss out on. The Matthew Effect shows the impact this approach to teaching has. Essentially, the poor get poorer and the rich get richer.

Regardless of ability all students are entitled to a broad curriculum that has depth. By not exposing all children to the subject terminology and vocabulary that is required, you widen the word gap, knowledge gap, and power gap in the future. All the gaps!

E D Hirsch argues that the acquisition of core knowledge is key to helping students understand and learn their vocabulary. Hirsch’s view of what knowledge actually is, is limited to say the least. Nevertheless, when it comes to historical vocabulary, he does have a point.

Questioning

One way we can help develop and consolidate this historical vocabulary is via classroom questioning. Here we must insist that they extend their oral answers. This could be as simple as recasting an answer to insist on key terminology.

Or, I might use fast paced questions to build the links by asking for specific key terms. A good technique for this is Doug Lemov’s book Teach Like a Champion 2.0. Its called Right is Right.

This sets the tone that we would wait for the completely right answer and that would be the response that incorporated key terminology and any new tier 2/3 vocabulary the students had been learning. For example:

Teacher: How did Hitler and the Nazis secure control by 1934?

Student 1: Posters

Teacher: What posters?

Student 1: Propaganda posters. They convinced people to support the Nazis.

Teacher: How did they do that?

Student 2: By indoctrinating.

Teacher: What else?

Student 3: The Terror. This created a fear that meant people supported the Nazis which meant they had more control.

Teacher: How?

Student 3: By using the Gestapo, SD, and the SS and ultimately the denunciations from informants.

Students 4: The removal of opposition both within and outside the party helped keep control as by 1934 the Nazis controlled the Reichstag, the courts, the Lander. They had full control.

This questioning is not finished – and of course surveying 4 students would not be particularly suitable AfL. However, you can see the questions build expectation so key terminology is being used and then developed to explicitly link back to the question.

This then allows you to build, not just for subject-specific terminology, but also connectives, linking phrases and ways to compare points. By hearing this and talking in this way the children will start to use this in their work. This won’t happen on its own though – you will need to make it explicit.

Indeed, this should be a key part of the whole school approach to literacy. As Jean Gross states in Time to Talk, one person can’t improve oracy a class at a time.

Hearing Historians speak

An interesting idea, for example, is to let them hear historians and academics talking.

There are lots of amazing documentaries that link to the curriculum, you can use this to consolidate knowledge and work on the premise that exposure over time will improve literacy. you can provide questions linking to specific terminology used and ask the students to link it to the meaning, or better yet, link it to the key term they already know.

For example, there is a wonderful In Our Time on the Spanish Armada and in it, there are two key moments that require students to consider language and link it to their knowledge on the Armada.

- Firstly, one historian refers to Spain as being like America and England like the Czech Republic. This opened up conversations about economy, power and democracy which most students had never heard. We then deliberately incorporated this into our writing about the importance of the Armada.

- Secondly, the historians all discuss how the Armada fits into the English identity ‘myth’. The students had to collect the vocabulary used by each historian to support their point of view on this identity. We then used the tools explored above to rate our confidence and link it to our pre-existing understanding of the Armada.

I hope these examples have shown that sticking on a documentary and expecting the students just to ‘get it’ isn’t going to happen.

You may end up widening the gap as some students can absorb it but others struggle, switch off, and start to believe that they just don’t get it.

There has to be a point to watching or listening to a documentary. This exposure to advanced vocabulary has to be placed at an appropriate point of the learning. It would be a special class that could have this activity as a way to introduce a topic; it should be reserved for when students are at the point that they can generalize about the content.

Can I have that in writing?

How to get the students to write extended pieces using key terms and command words is a well-trodden path and could be an article on its own.

Instead, I’m just going to share some ‘extras’ that will help you translate the excellent literacy work you have been doing into the students written work.

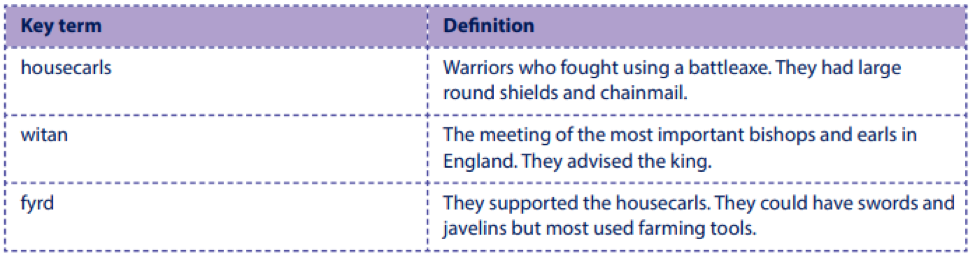

I recently adopted using SPED. Statistics, People, Events, Dates. This transformed the notes my students took and then it started to become evident in their extended writing and exam responses that they were focused on the key information (that we had built through word banks).

At first I scaffolded activities by showing where I would expect to see each element of SPED in notes. I frequently model the difference between notes that have used SPED and ones that have not – this then easily becomes an exercise on relevance.

| Notes Using SPED | Notes Not Using SPED |

| Catholic monarch | Mary was a problem |

| Claimed head of Scotland France and England | She was catholic and wanted to be on the English throne too |

| Figurehead for Catholic Plots (1569 Northerm, 1571 Ridolfi) | Elizabeth was worried that she would take the throne and focus on England |

| Focus for Phillip II of Spain | She spent time in various prisons on England. |

| Challenge the throne | Cost the people who housed her a lot of money. |

| Compromise the religious settlement | Sent messages in beer barrels |

| Cecil uses spy network – Walsingham | |

| Imprisoned after arrival 1568 | |

| … |

As you can see from the example, the notes using SPED are focused on the key people and events. I have also found over time that the evidence used in exam responses is much more relevant to the question because the students are not focusing on telling a story.

They know that Mary costing Shrewsbury loads of money is accurate but not relevant to why she was a threat to Elizabeth’s power.

They started doing better because they started adding in more relevant and accurate information that linked to our subject literacy expectations. So simple but so effective. I cry at the start of every activity: “think SPED!”.

Subject-specific scholarship

If you are part of the History teacher Twitter community, you will have seen – and possibly been overwhelmed by – the focus on using subject scholarship for comprehension and analysis.

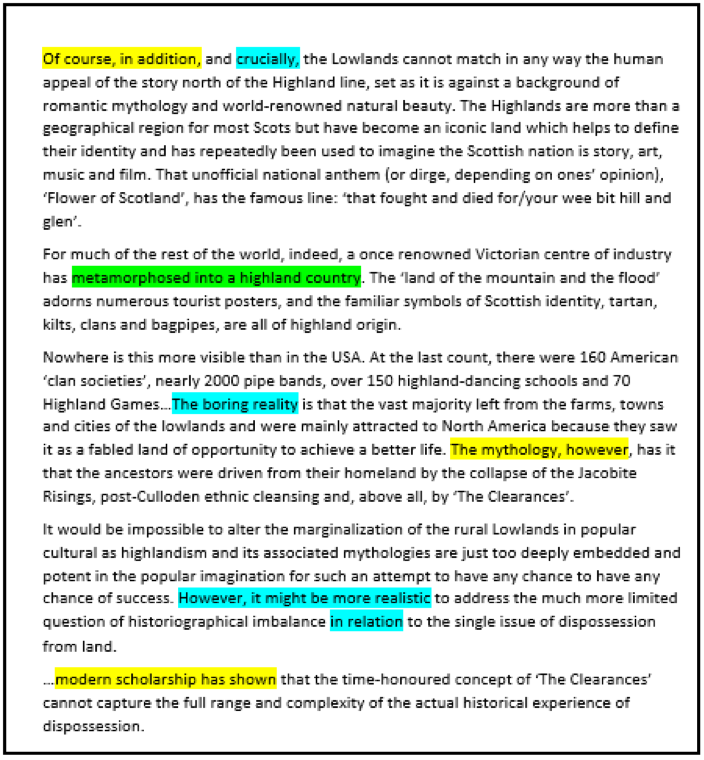

This is wonderful but I would remind you of the need for context and a strong foundation to build on before using this with a class. However, a great way of extended literacy is asking students to pick out the vocabulary used by Historians to do the following:

- Give examples

- Link back

- Make judgements

An example I used with students on the PGCE course at the University of Warwick recently was an extract of the new Tom Devine monograph, The Scottish Clearances. You can see where students would be expected to highlight the above.

By reading the piece, they are consolidating and extending their understanding – but, importantly, they are seeing how language is used. In my experience this won’t translate in student work straight away – it will take time and regular exposure.

As Alex Quigley argues in Closing the Vocabulary Gap: Literacy is everyone’s responsibility . In sharing these simple strategies, I hope I have shown you how you can make literacy a regular part of your classroom practice.

And, that it doesn’t have to be a distraction from the history. It can be something that is used as retrieval at the start of the lesson, or to consolidate throughout the lesson. It can freshen up the focus on extended writing – especially when using a spaced approach to revisit content.

As educators we have a duty to send children into the world literate and able to find their place. This must be led systemically but we can’t allow it to happen by chance in our classrooms. More than anything, language is the key to a date, a job, a better price on a car. It is also a way to express love, anger and frustration.

As History teachers we can help with that. Our subject is more than just preparation for pub quizzes in 15 years time!

Lindsay Bruce teaches History at Moreton School in Wolverhampton, part of the Amethyst Trust. She is an Assistant Head and is an author for OUP, contributing to the KS3 Aaron Wilkes series and the AQA GCSE student books, handbooks and revision guides.