Interpretations lie at the heart of history teaching. We are told that it is the jewel in its crown. The word encompasses an almost endless variety of materials.

To cite just one list, interpretations can be “pictures, plays, films, reconstructions, museum displays, and fictional and non-fiction accounts“. Readers can no doubt extend this catalogue further. And yet…

The problem with using text-based ‘historical scholarship’

Is it just about books and historical writing?

Take a glance through the literature and you’ll find that most often interpretation has meant “text” and that text has usually meant “trade book” (and a pretty narrow sample of trade books at that).

The desire to give pupils a feel for real History and authentic debates is understandable – albeit few academic historians actually write trade books and the new Open Access requirements of the Research Excellence Framework mean that number is likely to become fewer still – but it does make considerable demands on pupils.

Extracts from books need to be long enough to give pupils a sense of the authentic voice of the author and to show how they construct their arguments and marshal their evidence.

Even with careful guidance, pages of text and lengthy passages of prose can be daunting prospects for many pupils.

Assuming that pupils can successfully navigate the texts we give them, are we actually showing them what ‘real’ History looks like? Glance through the literature again and you’ll find the same small number of books being recommended repeatedly.

Obviously, certain types of writing will be more accessible, more engaging, and more thought-provoking than others.

Yet there is a risk that we are introducing pupils only to a narrow, and potentially unrepresentative, sample of historical writing.

There is also the question of context. Even a book as stimulating (and as down-right enjoyable) as the oft-recommended Voices of Morebath is already twenty years old and historical debates have not stood still in the interim.

Can we understand a work, can we grasp its distinctive contribution to knowledge, without an appreciation of its place within the broader scholarship?

This points to a larger problem.

With some notable exceptions, much of the research on interpretations has taken place in isolation from wider disciplinary trends. For example, there are obvious, albeit largely unexplored, affinities between work on interpretations and the broader field of Reception History.

None of this, of course, is reason not to introduce pupils to historical writing. But there is a positive case for looking beyond books, too.

Debates about the past and its meaning currently playing out in the media focus far less on the written word and far more on commemoration and curation.

Obvious examples here are the responses to the Black Lives Matter and Rhodes Must Fall campaigns or to the National Trust’s report on colonialism and historic links to the slave trade.

If History teaching is about honing pupils’ skills as “BS detectors” (as one editor of this site is fond of saying), then we need to equip them with the understanding and the expertise to navigate precisely this kind of terrain.

Museums and Interpretations

Recently I taught a mixed ability Year 8 class a unit exploring the transatlantic slave trade from its origins to the mid-19th Century.

I decided to devote the final four lessons of this unit to interpretations and opted to discuss museums and curation alongside texts.

This decision was based partly on topicality and pupil enthusiasm.

We had already discussed the debates about Edward Colston’s statue and other monuments to slave traders and pupils had clear ideas about the role that museums could play in all this.

We had also explored other ways in which the difficult past could be represented and interpreted and, again, pupils had responded well to these discussions.

I hoped, too, that familiarity would aid understanding.

Subscribe

Don't miss out - Sign up to receive the latest articles, resources and analysis direct to your inbox

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Museums are a commonly encountered interpretation: few pupils in Year 8 will have read an academic history book but many will have visited an exhibition or gallery, sometimes as part of a school trip.

But there were also good disciplinary reasons for such a focus. Despite museums often appearing in lists of interpretation types (such as the one given above), there has been little discussion in the literature about how we might go about exploring them in the history classroom.

This is particularly surprising given that the past few decades have seen dramatic changes in how museums are understood. This New Museology has led to greater reflexivity on the part of directors and curators and has drawn attention to museums as sites of interpretation rather than authoritative arbiters of knowledge. By exploring museums and curation, pupils could engage, albeit implicitly, with disciplinary advances of this kind.

The four lessons were taught during lockdown and online learning presented both problems and possibilities.

A class visit to a museum was not going to be possible but technology such as Google Slides and Jamboard provided more opportunities for creative work than were sometimes available in a physical classroom.

I devised three separate tasks intended to get pupils thinking about museums and curation as well as about the nature of interpretations more generally.

These activities were taught alongside tasks looking at written interpretations, with the hope that the two would be mutually reinforcing.

Task One: Curating an Exhibition

The first task was based on the idea – well-established in the literature – that pupils’ own interpretations can act as an ideal starting point for thinking about interpretations more generally.

Using Google Slides, pupils were given a set of 16 images, each featuring an object connected to the slave trade.

As well as chains, brands, and instruments of torture, these included such things as sugar tongs, a tobacco jar, and — stretching the definition of object to breaking point – an 18th Century cotton mill in Lancashire.

Pupils were asked to curate their own small exhibition on the transatlantic slave trade by selecting five of these object and writing short captions for each, justifying their inclusion.

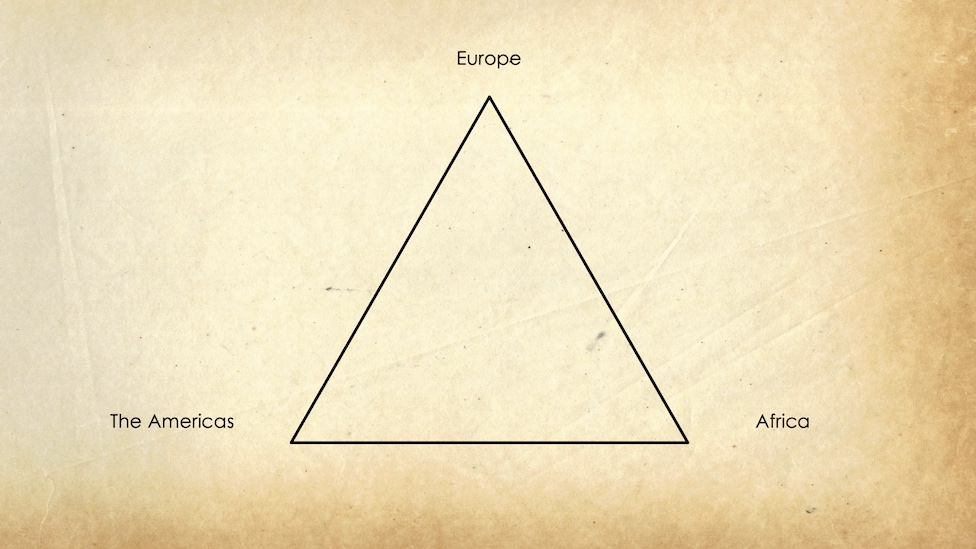

This was done by copying the chosen images onto a slide with a schematic diagram of the Triangular Trade and then using the Google Slides tools to add textbox captions.

This exercise had three basic aims.

The first was to encourage pupils to think about how collections of objects can tell stories or communicate ideas -that is, to think about how curation works at a very basic level.

The second aim was to help pupils to see that interpretations do not necessarily differ because of differing access to sources – a commonly-held misconception.

They were all creating their exhibitions – their interpretations – from the same set of objects, from the same sample of sources.

Interpretations most often differ through the weight that is given to different sources and through their selection, contextualisation, and presentation.

The final aim was to prompt pupils to consider the external constraints placed on interpretations – they could select only five objects for their exhibition.

Authors, artists and curators are very rarely free to structure their interpretations exactly as they would wish.

The publisher and editor, for example, will have considerable input into the word length of a trade book as well the number and type of illustrations it contains.

They will also likely decide whether or not the book has full references and a bibliography and whether the names of historians and other scholars are to feature in the body of the text.

A copy editor might shape the writing style of the author, while peer reviewers may demand changes to the content and a designer determine the overall layout and feel of the book.

Even the title may not be the original choice of the author.

As hoped, pupils produced a varied range of interpretations.

Some objects – particularly a whip and a set of shackles – featured in many exhibitions but otherwise there were marked differences in the items selected.

Though some pupils wrote only very brief explanatory captions, and some supplied none at all, others offered more detailed and thoughtful justifications for their selection.

I chose two exhibitions to discuss (after being anonymised) in the next lesson.

One interpretation emphasised the violence inherent in the slave trade and the dehumanising effect it had on its victims.

The other stressed the economic underpinnings of the trade and showed how it was driven by British demand for particular goods.

The differences between the two interpretations were readily appreciated by the pupils and they could summarise well the overall message of each exhibition.

Pupils also grasped the point – albeit with some prompting – that the same source materials could lead to very different, but equally valid interpretations.

Task Two: ‘Reading’ a Museum

The aims of the second task were more modest than those of the previous activity.

Firstly, I wanted to encourage pupils to start actively thinking about museums as interpretations and to note the contrasting ways that different institutions could approach the same subject.

Secondly, I wanted to see if pupils could read real world interpretations with the same facility as they had understood interpretations produced in class.

Pupils were shown images of objects and displays from the websites of the Wilberforce House Museum in Hull and the Liverpool International Slavery Museum.

Without being given any information about context or provenance and without being told the names of either of the two museums, pupils were asked what they could deduce about the focus and message of the two different institutions.

Based on the objects from its collections, pupils quickly grasped that the focus of the Wilberforce House Museum was likely to be on a single person.

Similarly, they offered suggestions as to how the museum would interpret the ending of the slave trade – placing emphasis on the role of important individuals rather than, say, economic factors.

By contrast, pupils suggest that the Liverpool International Slavery Museum had a broader focus and placed an emphasis on the achievements of the African diaspora and on the role played by slaves in their own emancipation.

In short, pupils proved themselves to be adept readers of museums.

Some even commented about the likely audiences and wider purposes of the museums.

Task Three: ‘Translating’ an Interpretation

The third task built on the basic methodology of the first activity. This time, however, pupils were not asked to produce their own interpretation from scratch. Rather, they were tasked with ‘translating’ a text into an exhibition.

Pupils had already spent some time analysing two written interpretations of the ending of slavery in the British Empire.

The first was an entry by Jordan Alexander in The British Empire: A Historical Encyclopaedia. The second was an extract from Tom Zoellner’s Island on Fire: The Revolt that Ended Slavery in the British Empire. Pupils could choose either of these texts as the basis for their exhibition.

Again, pupils were given a selection of 16 objects, different from those used in the first task, and had to choose five from these.

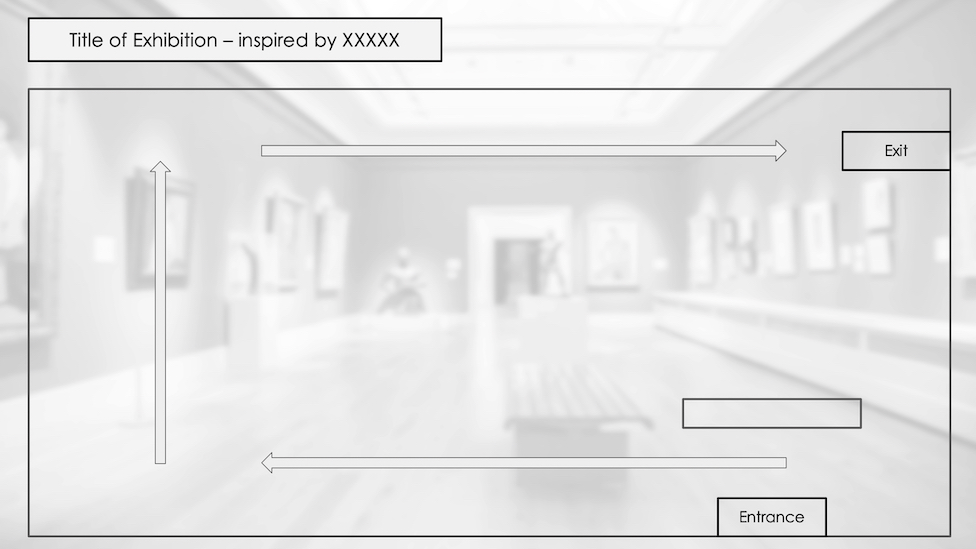

The exhibition space these objects were placed in – based loosely on a gallery in the Brighton Museum – had display boards as well as an entrance and an exit and so was more involved than that of the first task.

There were two aims with this activity. Firstly, I wanted to see how well pupils had understood the text that they had chosen. How successfully could they ‘translate’ it into an exhibition?

The second aim was to encourage pupils to think more about effect of the placement of objects within a gallery or exhibition.

What impact did the ordering of items have? Might certain locations within the space have particular prominence and how would this effect the overall message of an exhibition?

In comparison to the first two tasks, this activity was much less successful.

Though a small number of pupils did produce some very effective translations, and had clearly given some thought to the ordering and positioning of their objects, most pupils simply created their own interpretations of the ending of slavery – albeit that some of these were interesting and insightful in their own right.

The similarities between this task and the first activity probably explain why it was a relative failure.

Pupils were understandably confused when confronted with near-identical looking tasks and the kind of guidance and supervision possible in the classroom was not practical in an online setting.

Conclusions

The activities outlined here were introductory in intention and modest in scope — a small part of a wider investigation of interpretations.

But, overall, they seemed to be successful.

Pupils produced interesting exhibitions of their own, commented intelligently on work created by others, and showed that they understood something of the nature of interpretations more broadly.

Most encouragingly, pupils were clearly interested by the idea of museums and curation as forms of interpretation.

The volume of comments made in the online chat, the range of individuals contributing to discussions, and the speed of responses to questions all suggested engaged and attentive pupils.

Dr Martin J Ryan began his career as a lecturer and researcher in Early Medieval History and has recently completed a PGCE in Secondary History at the University of Sussex.